All stars, including the Sun, have a finite lifetime. Stars shine by the process of nuclear fusion in which lighter atoms, such as hydrogen, fuse together to create heavier ones. This process releases vast quantities of energy which counteracts the ever-present inward pull of the star’s gravity. Ultimately, fusion helps stars to resist gravitational collapse.

This balance of forces is called “hydrostatic equilibrium”. However, there will come a time when the supply of fuel in the core of a star starts to run out and it eventually dies. Stars with more than about eight times the mass of the Sun will typically burn through their fuel in less than 100 million years. Once fusion ceases, the star collapses – generating a massive instantaneous final burst of nuclear fusion which causes the star to explode as a supernova.

Supernovas release enough energy to outshine the entire galaxy in which they occur. What’s left afterwards are collapsed, dead stellar cores called neutron stars or, if the progenitor star was massive enough, a black hole. Any planets orbiting a star when it goes supernova would be obliterated. Mysteriously though, a handful of “zombie planets” have been detected orbiting neutron stars. And they are some of the weirdest worlds in the cosmos.

Neutron stars are extremely dense, containing as much mass as the Sun squashed into a sphere only a few miles across. Some neutron stars emit beams of radio waves into space – and it is around these “pulsar” stars that planets have been found. As the pulsar spins, its radio beams sweep through space generating regular radio flashes. Pulsars were discovered in 1967 – you can listen to the sounds of the radio emission from some of them here.

The regularity of these radio pulses make pulsars ideal for hunting nearby planets. If a pulsar has a planet, they will both orbit a shared gravitational centre. This means the radio emission will be periodically stretched and compressed in a predictable fashion – allowing us to detect the planet.

Phobetor, Draugr and Poltergeist

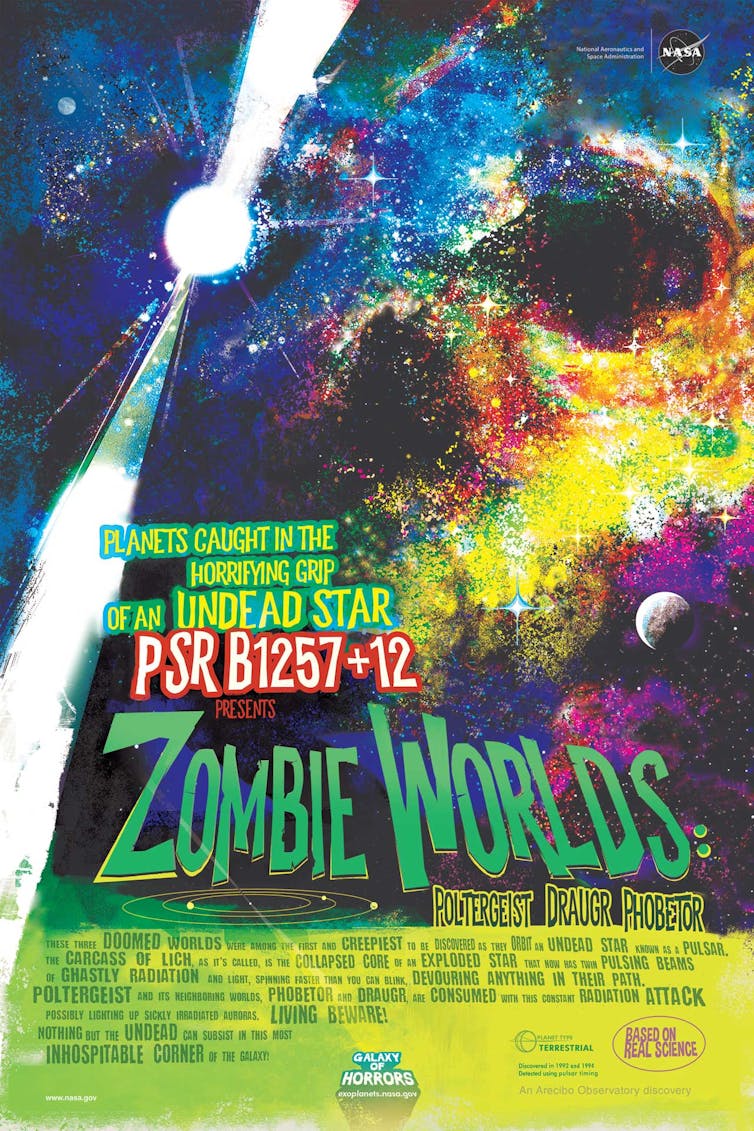

Some 2,300 light years from Earth lies the pulsar PSR B1257+12. It flashes 161 times per second and has been nicknamed “Lich” after an undead creature in western folklore. It is orbited by three rocky, terrestrial planets named Phobetor, Draugr and Poltergeist.

These planets hold a special place in the history of astronomy, as they were the first beyond our Solar System (exoplanets) to be discovered back in 1991. A few years ago, Nasa released this “zombie worlds” poster of them:

Their discovery challenged ideas about planetary formation, which normally takes place as a new star forms. In contrast, these planets must have formed after the dying star’s supernova. It is not yet known with certainty how this happened. Material in a disk of debris orbiting the pulsar may have coalesced into planets after the supernova.

Draugr, named after an undead creature in Norse mythology, is the innermost of the three. It has about twice the mass of the Moon and is the least-massive planet currently known, orbiting Lich every 25 days. Its larger cousins, Poltergeist and Phobetor, orbit every 67 and 98 days respectively, and are each about four times the mass of Earth.

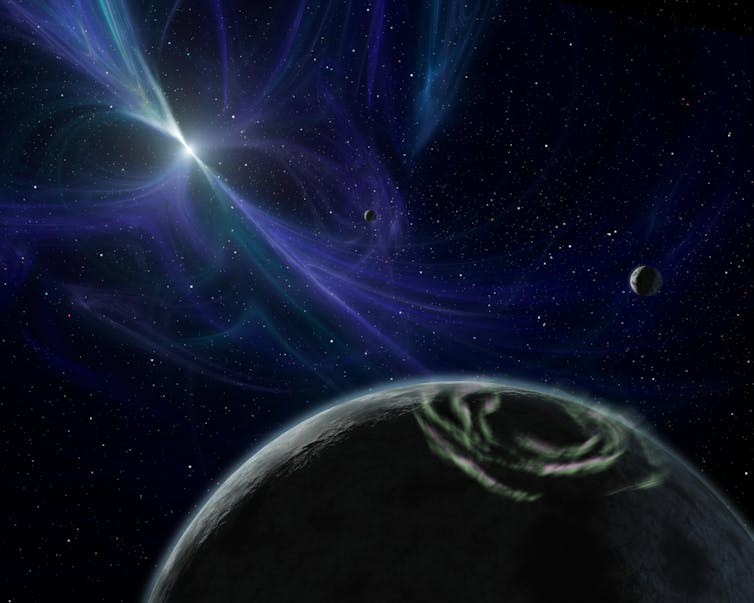

Pulsars have powerful magnetic fields which may allow electric currents to arc through space between the pulsar and an orbiting planet. So if any of these planets have atmospheres, they might constantly be bathed in the unearthly light of powerful aurora (similar to our northern lights).

If you were to stand on the surface of one of these zombie worlds, you would see, through the powerful hue of the aurora, the incandescent Lich in the sky projecting two powerful and tightly confined beams of light outwards in opposite directions into the blackness of space. Neutron stars can be extremely hot, carrying the residual heat left over from the supernova. Lich is nearly 30,000°C and the innermost of these worlds, Draugr, is likely to only be a few degrees below freezing at its surface.

Diamond world

Planet PSR J1719−1438b orbits a pulsar some 4,000 light years away, hurtling around its host in just over two hours. It is the densest planet yet discovered – so dense, in fact, that it is thought to be composed largely of diamond.

This “diamond world” is the remnant core of a dead star called a white dwarf. These are known to have a high carbon content (diamond is made of carbon) – but this particular white dwarf has lost 99.9% of its original mass, consumed by the powerful gravity of its nearby host pulsar.

This sphere of diamond is about half the size of Jupiter, and orbits PSR J1719-1438 at a distance of 600,000km (just 1.5 times further away than our Moon is from Earth). At such a close distance from its host pulsar, it is likely that this world has a very hot surface.

Methuselah

Orbiting the Milky Way (and many galaxies) are globular star clusters – spherical groups of up to a million stars each. These are some of the oldest stars in the universe.

The globular star cluster Messier M4 lies about 5,600 light years away and contains some 100,000 stars. Among these is a planet nicknamed Methuselah, after the son of Enoch in the Book of Genesis who supposedly lived for 969 years.

At the centre of the M4 star cluster is a pulsar and a white dwarf orbiting about their shared gravitational centre every 161 days. Given the short-lived nature of high-mass stars, the pulsar would have formed shortly after the formation of Messier 4 itself.

Methuselah also orbits this centre, but at a much more leisurely pace of once every 100 years or so, at a distance similar to that at which Uranus orbits our own Sun. It is a giant gas planet around 2.5 times the mass of Jupiter. Methuselah is believed to have formed as a normal planet around a Sun-like star within the first billion years of the formation of the universe. It was then captured into orbit around the host pulsar, which it has orbited ever since.

The high density of stars in globular clusters makes the chances of two stars having a close encounter quite high – and likewise the exchange of planets. Methuselah is the oldest known planet in the cosmos, having formed an estimated 12.7 billion years ago along with all the stars in M4.

Pulsar planets are worlds of extremes, yet even they may not be the most bizarre. A small number of theoretical studies have proposed the existence of planets orbiting black holes. So far, however, none have been found.

Gareth Dorrian, Post Doctoral Research Fellow in Space Science, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.