Ask a child to draw a picture of their house, and they will likely show the following: a lovely, humble abode where they and their family live and take shelter, plus maybe a few pets here and there. Add to that some surrounding trees or a street their house stands next to. Add a rainbow behind the house for good measure.

However, the large swath of blue that covers the space on top of the house roof remains static. Yes, there may be some clouds here and there, plus maybe a few birds for good measure and scientific accuracy—the blue remains constant, nevertheless.

These young minds may have found the time to ask their older siblings or parents the question perhaps as old as our own species’ set of two eyes: “Why is the sky blue?“

Now, some of you may have found yourselves in this very situation and were forced to come up with your answer to satiate the burning curiosity sitting in the back of the child’s mind; no need to worry, though, as we are ready to address the question to get you prepared for the next family reunion.

First Things First

Before anything else, there are a few things we need to consider, starting with a phenomenon called Rayleigh scattering.

Named after the British physicist John William Strutt, a 19th-century scientist perhaps better known for his title Lord Rayleigh, Rayleigh scattering occurs when sunlight interacts with the molecules and tiny particles in our planet’s atmosphere.

The thing is, sunlight isn’t just white light—and you’d probably know about this once you learned how rainbows form.

Light Up the Sky

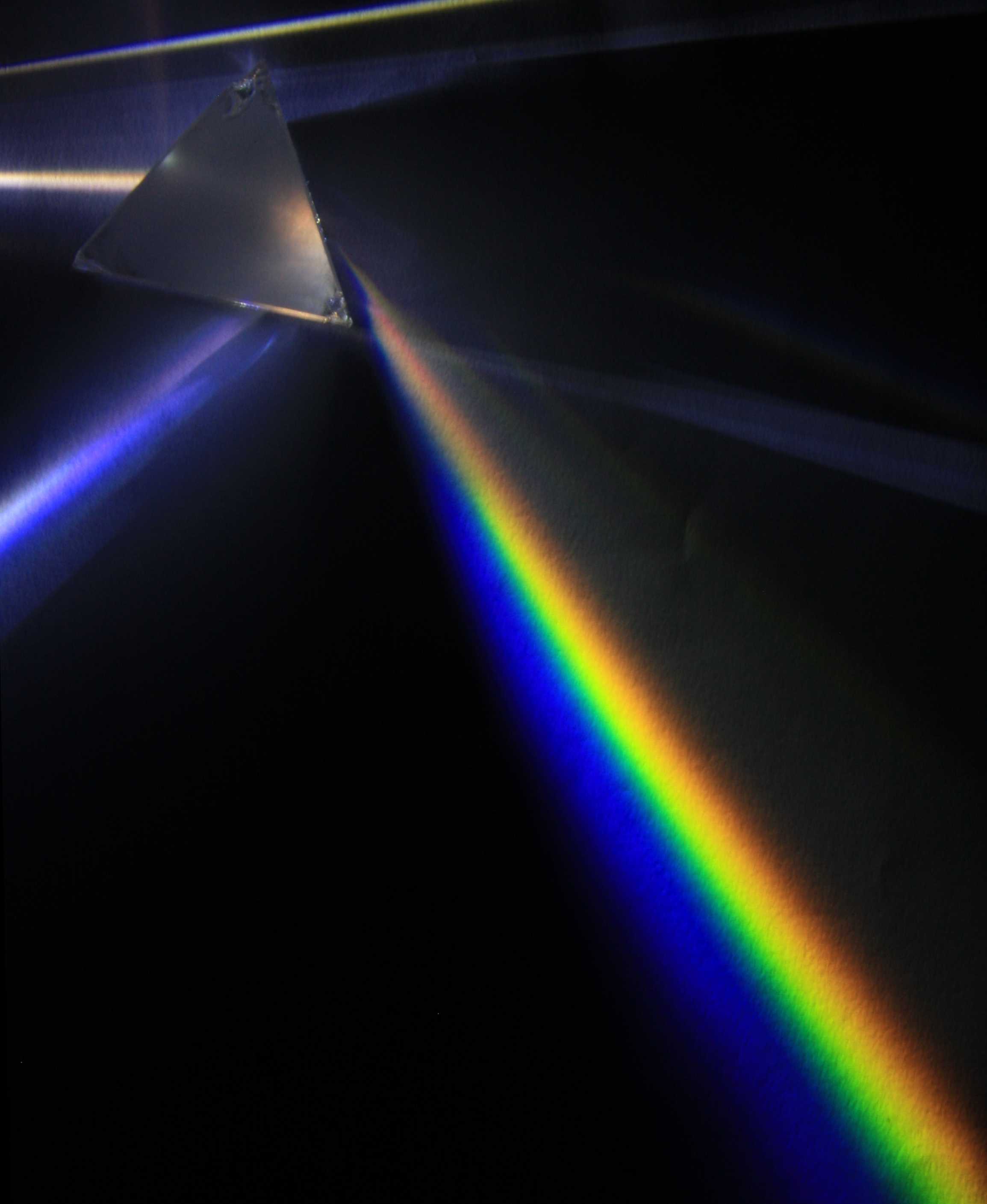

Sunlight, as it turns out, is not just one color but a mixture of various colors that form what we perceive as white light. You’d see this whenever sunlight passes through a glass prism—or perhaps a more naturally-occurring one in the form of millions of tiny water droplets, in the case of rainbows.

Now, light traverses through space in the form of electromagnetic (EM) waves (the whole wave-particle duality thing that light possesses), and visible light is classified within a particular “band” in the electromagnetic spectrum known as the visible spectrum.

What happens is that electromagnetic waves, and thus visible light waves, vary in energy, corresponding to the wavelengths they possess; generally speaking, less energetic waves travel with longer wavelengths, while more energetic ones travel with much shorter ones. (Scientists call this “inversely proportional.”)

In the visible spectrum, these wavelengths can be seen in the colors they emit; less energetic ones appear red, while more energetic ones appear blue, going towards violet.

This is why the rainbow is arranged the way it is—a prism (or, in this case, millions of water droplets) splits visible light into its component wavelengths, all with varying energies and thus colors. Hence, ROYGBIV. (Realistically, this should be more of ROYGCBV; the colors between green and blue appear cyan, while indigo and violet are practically the same).

This is also the reason why less energetic EM waves exist “below” red and outside the visible spectrum, hence why we only “feel” invisible infrared (“below red”) radiation as heat. In the same vein, this is also why ultraviolet (“beyond violet”) radiation is so dangerous to our skin, despite being invisible all the same—it’s more energetic than visible light and is thus “beyond” the visible spectrum.

Back to the Sky

One more thing to consider before we return to Rayleigh scattering: we need to talk about air molecules—or, more specifically, their size.

Unsurprisingly, molecules are so tiny that you can fit 2.7 × 1019 air molecules inside a cubic centimeter of air. This makes them the most likely to interact with the smallest wavelengths of visible light, which happens to be right where the blues and violets are in the visible spectrum.

That’s why it’s called Rayleigh scattering—air molecules interact with the smaller wavelengths of visible light and “scatter” them while letting the longer-wavelength portions pass through without much fuss. As a result, the blues of visible light and beyond are left to scatter in the surrounding air molecules, making the sky appear blue while the rest of the colors reach your eyes as white light.

One thing to note is that your eyes are much more sensitive to blue light than violet; this is why the sky appears blue instead of violet, despite the air scattering technically more violet light than blue. Besides, the Sun sends over more blues than violets, anyway (in the visible spectrum, at least).

A Surprise at Sunset

P.S. It’s also related to why sunsets appear orange or sometimes red!

Often, sunlight that passes through the atmosphere and has its blue wavelengths scattered doesn’t reach you directly. It’s why midday sunlight still appears bright and white, despite the blue skies above you—sunlight from an overhead sun passes through much less atmosphere on its way to you, meaning it doesn’t get its blues scattered as much as the rest of the light.

During sunsets, however, most of the sunlight has to pass through the atmosphere before reaching you. Plus, it’s reaching you from an angle (because it’s sunset, of course), so it has to pass through a lot of atmosphere on its way to you. By then, mostly the reds and oranges of sunlight remain, hence our favorite picturesque sunset hues.

Before We Scatter

Hopefully, the explanations above help you shower some science upon your nearest curious toddler whenever they ask about the vast skies. Sometimes, the simplest-sounding questions hide much science behind their answers.

And hey, maybe it helped shine some light on your doubts about how our world works. Some might say it’s a happy coincidence at that point—much like the rainbows that appear after a light shower.

References

- Gibbs, P. (1997). Why is the sky blue? UC Riverside Math; UC Riverside. https://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/General/BlueSky/blue_sky.html

- NOAA SciJinks. (n.d.). Why is the sky blue? NOAA SciJinks; NOAA. Retrieved 15 September 2023, from https://scijinks.gov/blue-sky/#:~:text=The%20Short%20Answer%3A,sky%20most%20of%20the%20time.

- Royal Museums Greenwich. (n.d.). Why is the sky blue? Royal Museums Greenwich; Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 15 September 2023, from https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/why-sky-blue

Thank you for making the topic more sinple and understandable for ordinary seniors like myself. My elementary and HS teachers always taught us that the oceans are blue because they reflect the color of the sky above but didn’t bother to explain whay the sky is blue in the first place. So now I know. Thanks.

My pleasure! It’s great to hear that people take even just a few nuggets of wisdom from our pieces. Cheers!