At the heart of the newest film in the Indiana Jones series lies “an ancient hunk of gears”. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is based around the Antikythera Mechanism: an actual ancient Greek object that tracked the cycles of the Sun, the Moon, and the planets against the stars.

The Antikythera mechanism and its bronze gearwheels totally reconfigured the study of ancient technology. It was among a bunch of other antiquities pulled out of a shipwreck by sponge divers in 1901. And it was tangible proof of a level of technological sophistication otherwise thought impossible for the first century BCE.

As a scholar of ancient Greek technology, seeing a blockbuster based around the Antikythera Mechanism is deeply satisfying. Moviegoers will leave the theatre with some facts about the Antikythera mechanism under their belt. Its fragmentary state. Its link to underwater archaeology. The complexity of the gears. The presence of Greek inscriptions. Its association with cosmology. The rival characters of physicist Voller and Jones even point to the way decoding the Antikythera mechanism has only been possible thanks to collaborations between science, archaeology, mathematics and ancient history.

As the movie progresses, the mechanism inevitably leaves the realm of history and enters fantasy. It becomes a time machine of sorts, used to predict “fissures in time”. Along the way, the film gives us a chance to reflect both on ancient technology in modern pop culture, and on our complex ongoing relationship with the Greeks and the Romans.

Archimedes and Nazis

The film begins with Nazi eyes initially set on a different object: the lance of Longinus. Once it is revealed the lance is a fake, there is some anxiety around how to present the far less snazzy relic of the Antikythera to Hitler instead. The sell for the film’s audience and for the Führer is Archimedes himself.

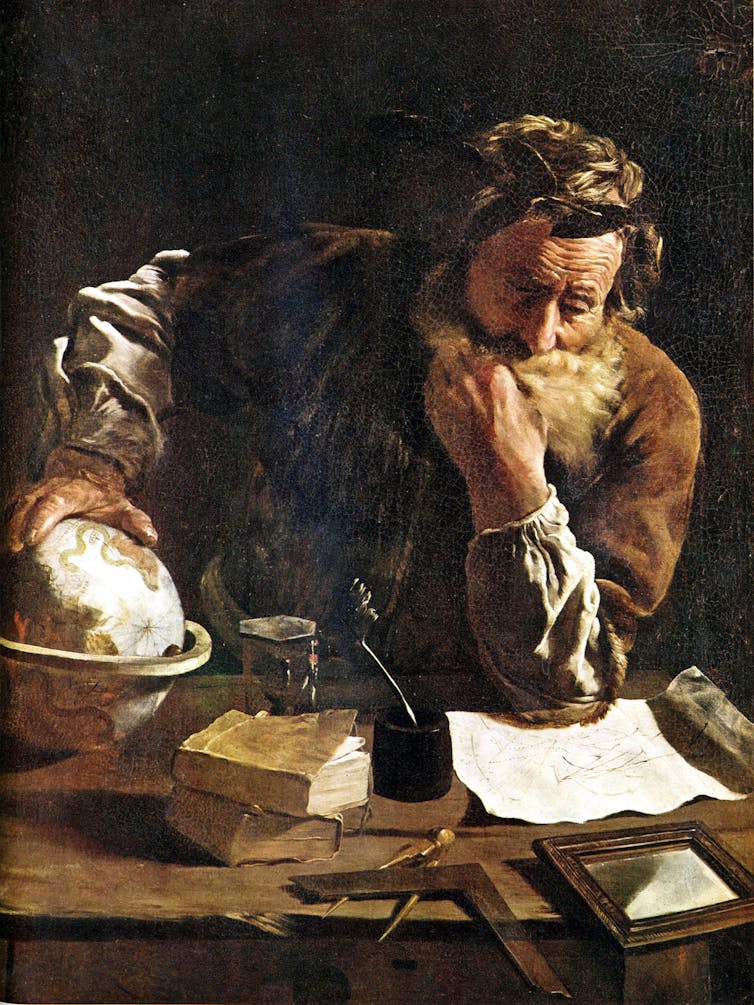

Today, this third century BCE mathematician from Syracuse is a household name. He is associated with inventions such as the Archimedes screw used to draw-up water in Assyria and Egypt. The eureka story accompanying his discovery of water displacement while taking a bath. Harnessing the power of the Sun to set Roman ships aflame. His theoretical dictum on the law of the lever. And as shown with Indie’s latest antics, the Antikythera mechanism can be added to the list of intriguing myths associated with the ancient mathematician.

In the film, Helena (Phoebe Waller-Bridge) steals the “device” in order to sell it at an illegal antiquities auction. Trying to hike up the price, Helena explains it was built by Archimedes himself. It’s one thing to attribute the design of the mechanism to Archimedes (some academic papers in fact toy with the same idea). But to imagine this renowned inventor figure physically putting the pieces of the gears together stretches even the best of the evidence. Notably, it completely removes the collaborative nature of ancient scientific practice.

It does, however, tell us a lot about how we tend to perceive ancient technology. It shows how badly we want to link historical inventions to a single genius from the past.

So what IS the Antikythera mechanism?

What survives of the mechanism is 82 bronze fragments – seven large and 75 small. Together these make up only one third of the original whole.

The Antikythera mechanism would not have been a disc as in the film, but rather a box covered in circles. On the back you could see two large spirals and three smaller dials which tracked the passing of time according to different calendars. There was also an inscription which acted as a kind of user manual.

On the front was large single dial of concentric circles with a number of pointers jutting out towards its very many inscribed segments. These pointers landed in different rings to indicate the phases of the Moon, the phases of the planets, the signs of the zodiac. Hiding inside this external shell was a complex arrangement of precision gears. These allowed a user to put the Antikythera mechanism into motion by carefully rotating a knob.

This portable machine was incredibly capable. It predicted eclipses according to a Babylonian cycle of the Moon. It reconciled various lunar cycles and three different types of calendar months. It matched the Greek zodiac scale with the Egyptian calendar.

This object brought together astronomical understandings from multiple cultures. It is physical proof of centuries of collaborative science.

The Antikythera mechanism, Hollywood, and Silicon Valley

Though this is the first time the mechanism has featured in a Hollywood blockbuster, the Antikythera has not been camera shy. From as early as the 1950s, the Antikythera mechanism was called a “computer” by scholars working on the device. This was quickly picked up by mainstream media.

In the last 15 years, the Antikythera mechanism has seen a revival of popular interest featuring in BBC Series, documentaries, articles (both scholarly and popular), YouTube videos as well as various museum exhibits around the world.

The common thread is that in looking at the Antikythera mechanism, you are looking at the “world’s first computer”. The same is often said of Homer’s Iliad predicting AI, and of ancient Greek automata being the world’s oldest robots.

This points to our obsession with drawing neat lines from the Greeks and the Romans to modern society.

Really, this tech saviourism does no-one any favours. It certainly does not do justice to the ancient object. It assumes that what drove ancient scientific pursuits is the same as what drives our own. It distracts us from understanding what the ancient object did in its context, how it was used, and what it meant to those using it.

Tatiana Bur, Lecturer in Classics, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.