The image of a lone Tyrannosaurus rex, famously shortened to T. rex, locked in combat with another dinosaur (such as Triceratops) as it tries to take down its prey, may be in for a shake-up: A study from the journal PeerJ published last April 19 suggests that members of the tyrannosaurid family may have hunted in packs, similar to how wolves hunt today.

The study details a recent find in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah, where a bed of roughly four or five fossil skeletons of Teratophoneus (teh-rah-tow-fow-nee-yus), a member of the tyrannosaurid family of dinosaurs which includes the eponymous T. rex, were found together with several fossils of fish, rays, and a 3.7-meter-long (12-foot-long) Deinosuchus (an ancient crocodilian related to the modern-day alligator). The fossils were discovered in the late Campanian-age Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah, a site given the delightful nickname of the “Rainbows and Unicorns Quarry” due to the sheer amount of key finds the site has yielded through the years. The most plausible explanation for the death of these tyrannosaurids currently accepted by the scientists is that the five Teratophoneus individuals were believed to have been killed at the same time by a seasonal flooding event, and were subsequently washed into a nearby lake where they were eventually buried under sediment before the body of water evaporated away. (The other animals were believed to have died from a separate event, and only the Teratophoneus specimens died together.)

The fossil dig site, the first tyrannosaurid mass death site discovered in the southern United States, seems to challenge the common assumption among scientists that tyrannosaurids hunted mostly alone, saying that dinosaurs lacked the cognitive capacity for parasocial hunting behaviors.

The method and the specimens

The scientists used physical and chemical analysis on rock samples on the site, with concentrations of rare earth elements along with analysis of stable carbon and oxygen isotopes revealing “relatively homogeneous signatures”—a telltale sign that the Teratophoneus specimens likely both died at and were fossilized at the same time.

The simultaneous death of these dinosaurs implies that they traveled together to where they were eventually killed, providing more evidence to the theory of their parasocial hunting behaviors and a stark contrast to the long-held notion that these animals were incapable of such. The recently-discovered fossil bed was also not the first time several tyrannosaurid fossils were found in one area; a bed of 12 Albertosaurus specimens were found in Alberta, Canada back in 1910, while 3 Daspletosaurus (das-plee-tow-saw-rus) specimens were found together in one fossil dig site back in 2005. Both Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus were genera under the Tyrannosauridae family, together with the previously-mentioned Teratophoneus, T. rex, and other genera such as Tarbosaurus.

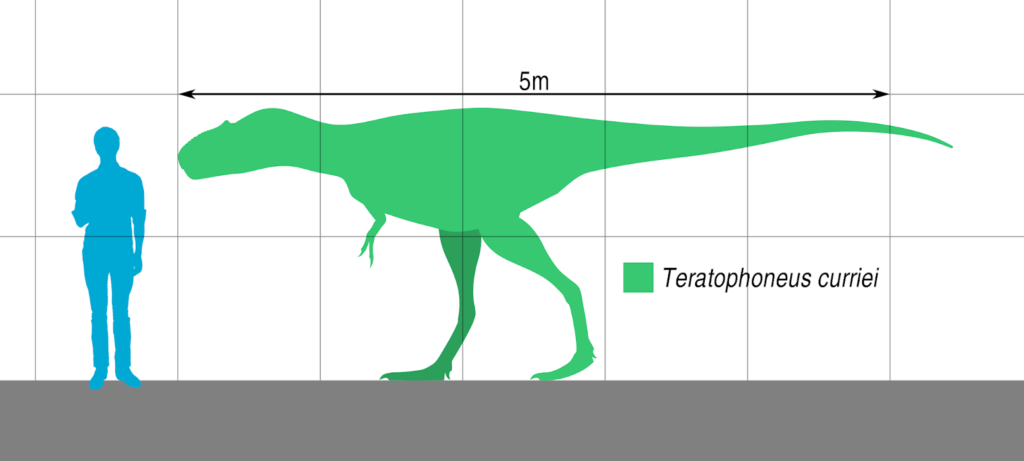

The genus Teratophoneus is currently known from only one species, Teratophoneus curriei, with the largest specimens measuring between 6.4 and 7.9 meters (21 and 26 feet) long. (By comparison, the largest T. rex specimen ever discovered reached 12.3 meters (40 feet) in length.)

The future

Said Kristi Curry Rogers, a biology professor in Macalester College, Minnesota, to the Associated Press: “It is a little tougher to be so sure that these data mean that these tyrannosaurs lived together in the good times. It’s possible that these animals may have lived in the same vicinity as one another without travelling together in a social group, and just came together around dwindling resources as times got tougher.” Modern-day vultures operate with similar behaviors, with several individuals scavenging on the same sources of carrion while hardly qualifying as an organized group.

The group responsible for the study, however, considers this find a highlight of their careers. As Alan Titus, a paleontologist for the Bureau of Land Management and discoverer of the dig site back in 2014, told a group of reporters during a virtual conference announcing the news: “I consider this a once-in-a-lifetime discovery for myself. […] I probably won’t find another site this exciting and scientifically significant during my career.”

(Photos from the dig site can be found in the team’s Flickr album.)

Bibliography

- Associated Press. (2021, April 19). Tyrannosaurs may have hunted in packs like wolves, new research has found. The Guardian. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/apr/19/tyrannosaurs-may-have-hunted-in-packs-like-wolves-new-research-has-found

- Black, R. (2011, May 19). Tarbosaurus Gangs: What Do We Know? Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/tarbosaurus-gangs-what-do-we-know-175546646/

- Dvorsky, G. (2021, April 21). Discovery of Mass Death Site Bolsters Theory That Tyrannosaurs Hunted in Packs. Gizmodo. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://gizmodo.com/discovery-of-mass-death-site-bolsters-theory-that-tyran-1846721350

- Eilperin, J. (2021, April 20). Tyrannosaurs likely hunted in packs rather than heading out solo, scientists find. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2021/04/19/grand-staircase-tyrannosaur/

- Possible evidence of gregarious behavior in tyrannosaurids. (1998). Gaia, 15, 271-277. https://doi.org/10.7939/R3348GX03

- Sommerlad, J. (2021, April 21). Tyrannosaurs may have hunted in packs like wolves, new research suggests. The Independent. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/tyrannosaurus-rex-dinosaurs-wolves-packs-b1834280.html

- Titus, A. L., Knoll, K., Sertich, J. J.W., Yamamura, D., Suarez, C. A., Glasspool, I. J., Ginouves, J. E., Lukacic, A. K., & Roberts, E. M. (2021, April 19). Geology and taphonomy of a unique tyrannosaurid bonebed from the upper Campanian Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah: implications for tyrannosaurid gregariousness. PeerJ, 9, e11013. 10.7717/peerj.11013