The emu is iconically Australian, appearing on cans, coins, cricket bats and our national coat of arms, as well as that of the Tasmanian capital, Hobart. However, most people don’t realise emus once also roamed Tasmania but are now extinct there.

Where did these Tasmanian emus live? Why did they go extinct? And should we reintroduce them?

Our newly published research combined historical records with population models to find out. We found emus lived across most of eastern Tasmania, including near Hobart, Launceston, Devonport, the Midlands and the east coast. However, in the early days of British occupation, colonists hunting with purpose-bred dogs slaughtered so many emus that the population crashed.

It’s not all bad news, though. Those areas still provide enough good, safe emu habitat to make reintroducing emus from the Australian mainland to Tasmania a realistic option.

Large animals, such as bison, wolves and giant tortoises are already part of global efforts to repair and maintain ecosystems and prevent more extinctions, through the conservation movement known as “rewilding”.

In Tasmania, rewilding with emus might help native plants to cope with a changing climate. As our world warms, the places where conditions are just right for particular plant species are shifting. Those plants must disperse far and fast to keep up. Introducing emus, which disperse many plant seeds in their droppings, could help.

Emus were Tasmania’s biggest herbivores

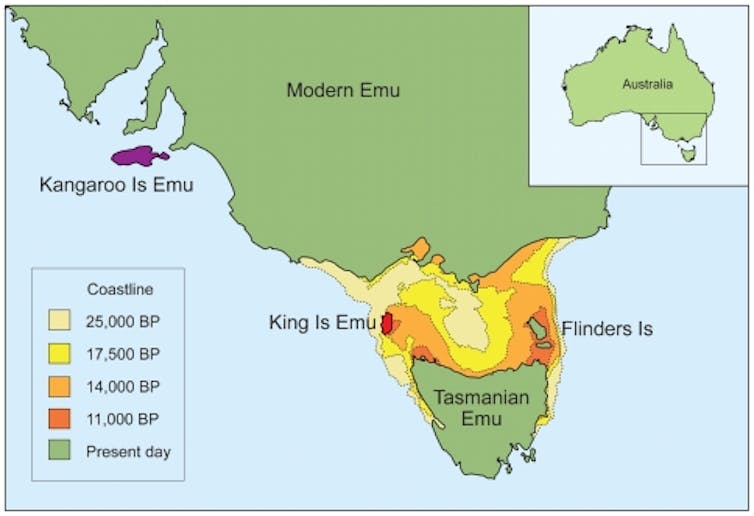

Emus are the biggest birds in Australia. The females weigh up to a whopping 37 kilograms. But when European sealers and explorers arrived on Australia’s southern islands, they found smaller, shorter emus. According to one estimate, Kangaroo Island emus averaged 24-27kg and King Island emus a mere 20-23kg.

Contrary to local folklore, Tasmanian emus were actually more similar to their mainland cousins. They weighed about 30-34kg (but sometimes up to 40kg).

Along with eastern grey kangaroos, known locally as “foresters”, emus were the biggest herbivores in Tasmania.

What are the likely impacts on ecosystems?

Large herbivores play important roles in ecosystems around the world. By chewing on plants, pushing through vegetation and churning up soil, large animals can create a mosaic of habitat types for other, smaller creatures. They move seeds and nutrients across the landscape and shape the frequency and intensity of fires.

Exactly how emus help ecosystems is a bit of a mystery because so few researchers have looked into it. But we do know emus are very good at seed dispersal. Emus live anywhere, eat anything and swallow their food whole. They walk miles and miles while seeds slowly pass through their gut, to be ejected in a ready-made batch of compost.

Without emus, some plant populations won’t be able to disperse quickly enough to escape the local effects of global warming.

How did Tasmania lose its emus?

We know colonists hunted emus and kangaroos in Tasmania. Emus were rarely seen on the island after 1845. But was hunting by a few hungry settlers enough to take out the whole population?

To find out, we recreated the emu population using computer simulations. Then we turned up the hunting pressure.

The signal was clear. Tasmania’s emu population could not sustain a harvest of more than about 1,500 adults per year. This limit was probably exceeded within a decade or two, which makes over-hunting the most likely cause of extinction.

Interestingly, the results of the simulation imply the island’s Indigenous people hunted adult emus at very low rates, less than one per person per year.

Where can we reintroduce emus?

To find safe places for reintroductions, we overlapped emu habitat with current land use. We found large parts of the state that have both good emu habitat and a healthy distance from areas with higher risk of human-emu conflict.

Small-scale, trial introductions could be done in fenced enclosures to learn more about the emus’ needs and their ecological roles.

Indigenous voices are particularly important in conversations about reintroductions, because of the roles such animals play in living traditional cultures. For example, emus have featured in Tasmanian Aboriginal story, dance, song and art for generations. Pakana and Palawa still perform emu dances today.

Such conversations must be had with care, because many Indigenous people are wary of terms such as “rewilding” and “wilderness”. These terms can carry the implication of a land without people, when in fact Australian landscapes have a long and rich history of Indigenous people caring for Country. Even the concept of “wildness” can imply too strong a separation between humans and our non-human kin, and a lack of reciprocity and responsibility.

Australia has just begun rewilding

Landscapes all over the world have lost large animals that would otherwise be keeping ecosystems healthy and dynamic. European and American conservationists have responded by reintroducing large animals for their ecological and cultural functions.

Rewilding Europe, for example, has reintroduced bison to the Carpathian mountains and primitive horses to Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria and Ukraine. These efforts are placing prehistoric grazing regimes back into a rich cultural landscape.

On islands in the Indian Ocean, giant tortoises have been introduced to replace their extinct cousins. Those tortoises graze down weeds and give native plants a better chance of recovery.

In Siberia, the Pleistocene Park project aims to re-create a rich steppe ecosystem by reintroducing bactrian camels, musk oxen and American plains bison. One benefit is this will increase the amount of carbon stored in that landscape.

In Australia, most of our animal reintroduction programs are focused on conserving individual species. In a few cases, like the Marna Banggara project, ecological engineers like bettongs are being introduced to kick-start ecosystem restoration, but this is happening behind fences and on islands.

We need solutions like rewilding for our open landscapes. Reintroducing emus to Tasmania would be a good first step.

Tristan Derham, Research Associate, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH) Policy Hub – Training and Education, University of Tasmania; Christopher Johnson, Professor of Wildlife Conservation, University of Tasmania, and Matthew Fielding, Research Associate / Teaching Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH), University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.