Imagine setting foot in South America and seeing mountainside caves sprinkled across the continent; some stretch far beneath the mountain peaks, with branches shooting off from the wide entry point. You also know these caves have been here far before humans have set foot on the so-called “New World.” Add to that that these caves exhibit rough impressions of what you think are claw marks. What made these caves if it weren’t people who carved them out?

These caves were not formed by natural processes but rather by the actions of giant mammals whose fossils have been described for over 200 years, shedding light on their fascinating lives and the ecosystems they once inhabited. One such type of animal commonly attributed to these cave networks is giant ground sloths.

Giant ground sloths belong to the clade Xenarthra, including today’s modern sloths, anteaters, and armadillos. Through proteomics analyses of bone collagen, scientists have determined the molecular phylogeny of these sloths. For example, proteomics-based sequencing revealed that Lestodon and Megatherium, two extinct giant ground sloths, are sister taxa to extant sloths. This means that they share a common ancestor and are more closely related to each other than to other sloth species.

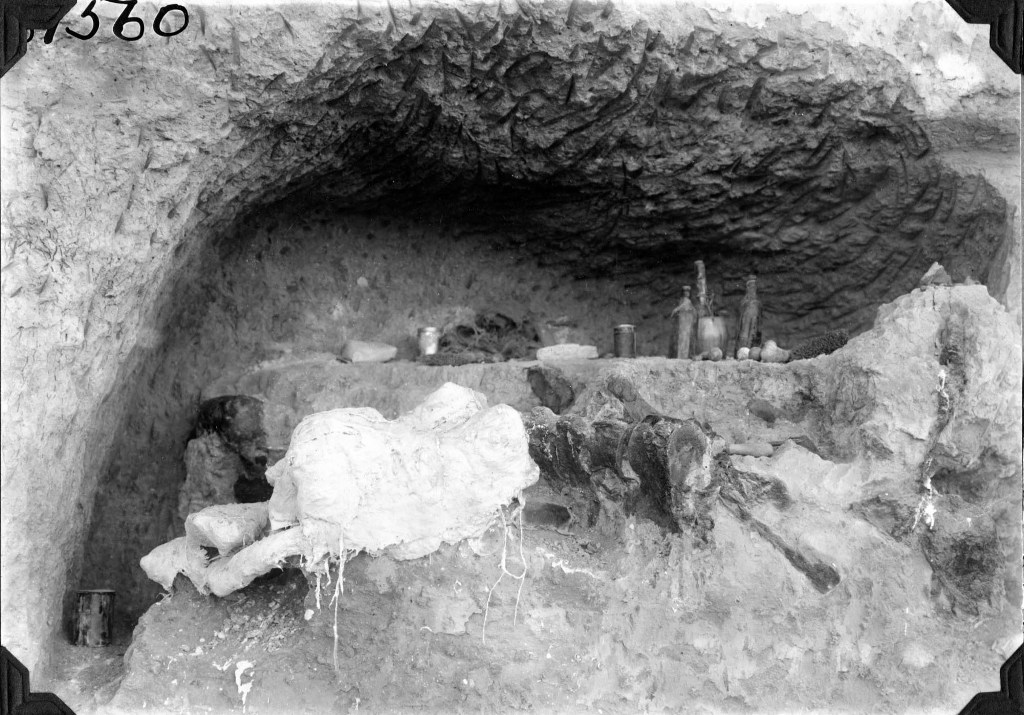

The fossil record of giant ground sloths in South America is rich, with numerous caves containing their remains. The Upper Ribeira Valley in southeastern São Paulo, Brazil, is one such area with an abundant fossil record of Pleistocene-Holocene South American megafauna. Fossils of giant ground sloths, such as Eremotherium laurillardi and Nothrotherium maquinense, have been found in this region. These fossils provide valuable insights into the past environments and climate of the area.

The diet of giant ground sloths has been debated among scientists. Stable carbon isotopic composition has been used to trace the trophic level of these sloths. Studies have shown that the carbon isotopic composition of their bones indicates an herbivorous diet. Fossilized dung, known as coprolites, has provided further evidence of their plant-based diet. Analysis of coprolites revealed that giant ground sloths consumed various plants, including yuccas, agaves, Joshua trees, globe mallows, mesquite, and cacti.

Sloth coprolites have provided valuable information about the behavior and ecology of giant ground sloths. These coprolites have been found in various caves across North and South America and the West Indies. They offer insights into the diet and habitat preferences of these sloths. Sloth coprolites in caves suggest that these animals may have used caves for reproduction, obtaining nutrients, shelter, and low metabolism.

In Peru, species of giant ground sloths have been discovered in caves. Megatherium celendinense is one of the largest Andean Megatheriinae species, characterized by its unique anatomical features. The discovery of this species extends the paleogeographic distribution of the Megatherium genus in South America. These findings contribute to our understanding of sloth morphological evolution, biogeography, and diversification history.

During the Late Quaternary Extinction event, South America experienced a significant loss of its late Pleistocene megafauna, including giant ground sloths. The causes of these extinctions have been debated, with human arrival and climatic changes being the main focus. Chronological information is crucial for estimating the timing of these extinctions. Recent studies have provided updated analyses of late Pleistocene mammalian deposits, shedding light on the timing of extinctions and the potential overlap with human arrival.

In conclusion, the study of giant ground sloths has given us a glimpse into the past, allowing us to reconstruct their lives and understand their place in ancient ecosystems. Through the analysis of fossils, proteomics, stable isotopes, and ancient DNA, scientists continue to unravel the mysteries of these incredible creatures. The story of giant ground sloths is a testament to the diversity and complexity of life on Earth throughout history.

References

- Bocherens, H., Cotte, M., Bonini, R. A., Straccia, P., Scian, D., Soibelzon, L., & Prevosti, F. J. (2017). Isotopic insight on paleodiet of extinct Pleistocene megafaunal Xenarthrans from Argentina. Gondwana Research, 48, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2017.04.003

- Buckley, M., Fariña, R. A., Lawless, C., Tambusso, P. S., Varela, L., Carlini, A. A., Powell, J. E., & Martinez, J. G. (2015). Collagen Sequence Analysis of the Extinct Giant Ground Sloths Lestodon and Megatherium. PLOS ONE, 10(11), e0139611. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139611

- Delsuc, F., Kuch, M., Gibb, G. C., Karpinski, E., Hackenberger, D., Szpak, P., Martínez, J. G., Mead, J. I., McDonald, H. G., MacPhee, R. D. E., Billet, G., Hautier, L., & Poinar, H. N. (2019). Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths. Current Biology, 29(12), 2031-2042.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043

- Ghilardi, A. M., Fernandes, M. A., & Bichuette, M. E. (2011). Megafauna from the Late Pleistocene-Holocene deposits of the Upper Ribeira karst area, southeast Brazil. Quaternary International, 245(2), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2011.04.018

- Lucas, S. G., & Sullivan, R. M. (n.d.). Fossil Record 6 Volume 1. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=EFfPDwAAQBAJ

- Pujos, F. (2006). MEGATHERIUM CELENDINENSE SP. NOV. FROM THE PLEISTOCENE OF THE PERUVIAN ANDES and THE PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF MEGATHERIINES. Palaeontology, 49(2), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00522.x

- Pujos, F., & Salas, R. (2004). A new species of Megatherium (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Sacaco and Tres Ventanas, Peru. Palaeontology, 47(3), 579–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00376.x

- Senckenberg Research Institute & Natural History Museum. (2017, April 18). The giant sloth megatherium was a vegetarian. Phys.Org. https://phys.org/news/2017-04-giant-sloth-megatherium-vegetarian.html

- Villavicencio, N. A., & Werdelin, L. (2018). The Casa del Diablo cave (Puno, Peru) and the late Pleistocene demise of megafauna in the Andean Altiplano. Quaternary Science Reviews, 195, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.07.013