On Jan. 24, history was again made when the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ organization moved the seconds hand of the Doomsday Clock closer to midnight. It is now at ‘90 seconds to midnight,’ the closest it has ever been to the symbolic midnight hour of global catastrophe.

The announcement, made during a news conference held in Washington D.C., was delivered in English, Ukrainian and Russian. The released statement described our current moment in history as “a time of unprecedented danger.”

The hands of the Doomsday Clock are set by the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. These leading experts focus on the perils posed by human-made disaster threats, which emanate from nuclear risk, climate change, biological threats and disruptive technologies.

The Doomsday Clock is the most graphic depiction of human-made threats, and the act of moving the clock forward communicates a clear and urgent need for vigilance.

For 2021 and 2022, the clock’s hands were set at 100 seconds to midnight. Since this time-keeping exercise began in 1947, the announcement on Jan. 24, 2023 represents the closest the clock has ever been to midnight — a clear wake-up call.

Threats over time

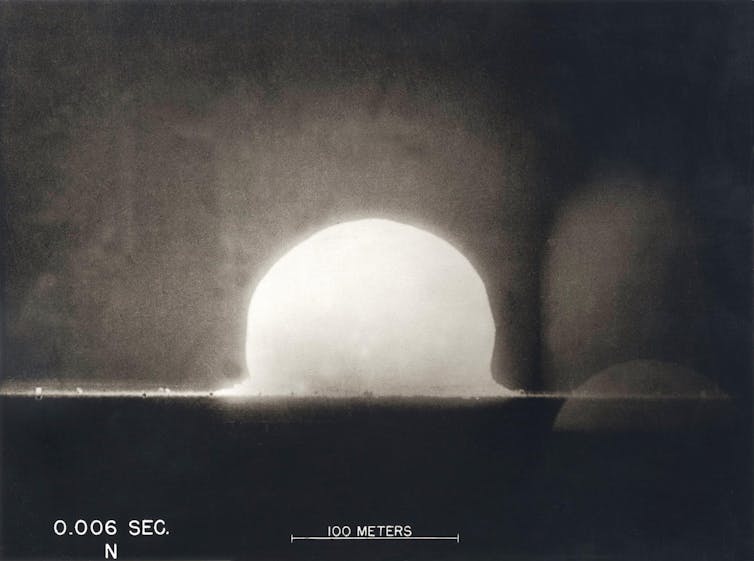

In 1945, a group of scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project — a United States research project into atomic weapons — joined together to form the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

In the late 1940s, the new threat of atomic weapons cast a dark cloud over the world. The Doomsday Clock was meant to be a warning to humanity about the dangers of nuclear weapons; later in the 20th century it was expanded to consider other human-made threats.

In 1991, the clock was set at 17 minutes to midnight, the furthest the clock has ever been from doomsday. This move followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty by the United States and Russia. In the 1990s, the world felt somewhat safer for a few years.

The 2010s brought the world closer to the brink of nuclear war than at any time other than the present.

U.S. relations with other global nuclear powers like Russia and China became increasingly tense. The Iran nuclear deal was abandoned, affecting the geopolitics of the Middle East. The threat from North Korea’s nuclear arsenal entered an alarming new phase. Along with the dangerous rhetoric of former President Donald Trump and the global rise of the far right, the stage was set for the 2020s to be a tumultuous decade.

In 2023, the global crises we are currently contending with have devastatingly broad consequences and potentially longer-lasting effects. Our current moment is unsustainable, especially as catastrophic threats multiply and intensify.

Layered crises range from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine involving Vladimir Putin’s thinly veiled nuclear threats to the social and economic strains still present at the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic. These are unprecedented challenges to human survival.

Apocalyptic anxieties

As the Doomsday Clock is now set at 90 seconds to midnight, the situation adds stress to an already anxious global populace.

In Europe, fears of COVID-19 were rapidly replaced by fears of a nuclear war.

Death anxiety — produced by a fear of dying — is related to nuclear anxiety, and the threat of nuclear war provoked by daily headlines could shape the way we think and act.

Nuclear weapons prompt a special existential anxiety, as weapons of mass destruction have the potential to eradicate entire cultures, lands, languages and lives. In the case of a nuclear attack, the future would be altered in a way that becomes inconceivable for us to process.

Philosopher Langdon Winner wrote that “during the post-World War II era, in a sense all of us became unwitting subjects for a vast series of biological and social experiments, the results of which became apparent very slowly.”

For those who grew up during the mid-20th century peak of the Cold War, and into the early 1980s, the resurgence of these worries carries a distinct tinge of déjà vu. To counter this recurring dread, coping tools include limiting media exposure, reaching out to others, cultivating compassion and changing your routine.

The time to act is now

The significance of the Doomsday Clock as a metaphorical time-keeping exercise serves as a graphic symbol of human-made multiplying perils. As the time to midnight has drawn closer, the urgency of the threat is intensified.

Whether or not one lives in one of the nine nations in possession of nuclear weapons, we have all become unwitting subjects of the experiment that began with the detonation of the first atomic weapon.

In 2023, the Doomsday Clock tells us that we are now 90 metaphorical seconds away from self-produced extinction. Time is of the essence.

Jack L. Rozdilsky, Associate Professor of Disaster and Emergency Management, York University, Canada and Christian Faize Canaan, Master’s student, Disaster and Emergency Management, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.