No, that’s not a Star Wars joke; there was a time—a long time ago, in a continent far, far away to perhaps some of you—when the field of paleontology was rife with bursts of competition, rivalry, and perhaps even sabotage.

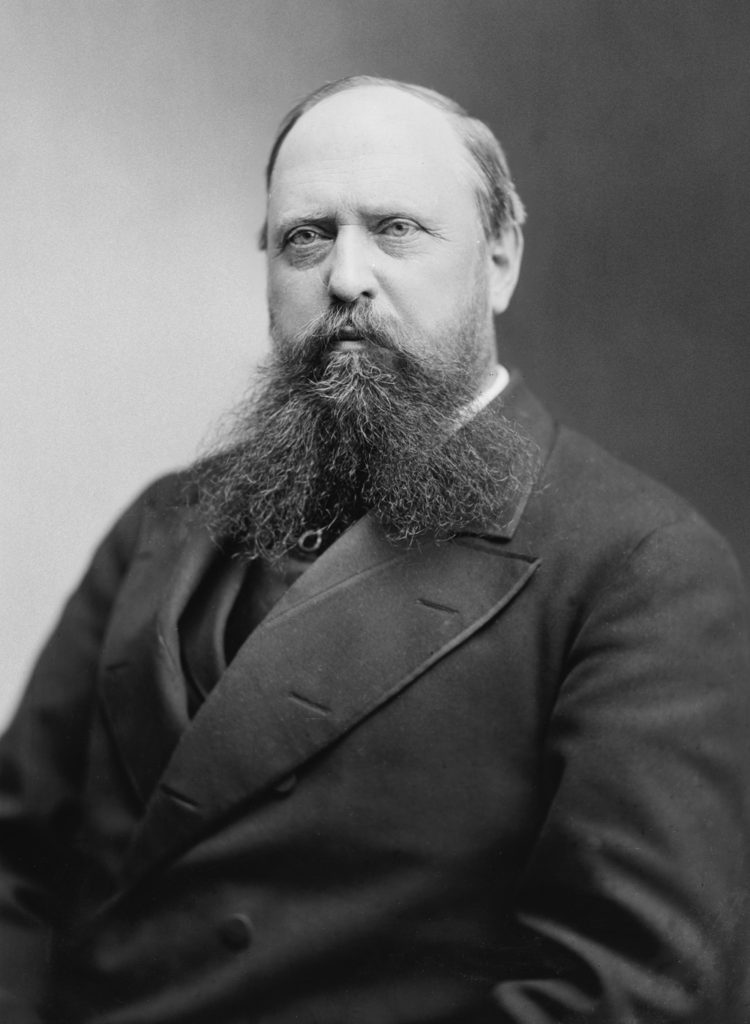

Scientific fields had their own individual “stars,” so to speak; persons whose contributions were so great that one cannot think of the field without their work. Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, Marie Curie, Alan Turing—their names alone would evoke images of intense work resulting in great advances in physics, evolutionary biology, chemistry, and computer science, respectively. In paleontology, however, the designation would perhaps belong to two men who, if alive, would probably resent the fact that their names would appear together at all. The two men were paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh.

The two, who unfortunately lacked a sense of cooperation at the time, would be locked in an academic “competition” for nearly two decades; what came out of those years—now coined the “Bone Wars”— were two financially and socially broke men. It also yielded more than 136 new species of dinosaurs, caused both rivals’ names to be listed as pioneers of paleontology, and ignited a spark of interest in finding new dinosaurs that would continue to this day.

The Tale of the Tape

Cope, born and raised in Philadelphia, U.S.A., grew up with a wealthy family, and ended up becoming a naturalist despite his father’s cries for him to become a farmer instead. His knowledge of the field would be enough to net him a professorial position in zoology at Haverford College, as well as a membership into the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Marsh, on the other hand, was born in Lockport, New York, U.S.A.; as the son of a struggling family, he grew up relatively poor. His philanthropist uncle, George Peabody, supported him through the years, to the point of building for Marsh his own museum—the Peabody Museum of Natural History—out of Marsh’s own request. Marsh eventually received some of Peabody’s inheritance once he passed away, leaving Marsh financially equipped.

The two paleontologists had actually collaborated before, and amicably so; the two had met prior in Berlin, Germany, back in 1864. Their relationship would sour over time, though, and was anecdotally attributed to a clash of their personalities. According to author David Rains Wallace in his book The Bonehunters’ Revenge: “Their disparate backgrounds predisposed them to look down, subtly, on each other. The patrician Edward may have considered Marsh not quite a gentleman. The academic Othniel probably regarded Cope as not quite a professional.”

They got along well enough then that in 1868, Cope actually invited Marsh to a fossil dig out in southern New Jersey. What the two weren’t aware of at the time was that the stage had been set for the clash of the two paleontology titans: it was in the middle of the Gilded Age of American history, in one fateful expedition to a marl pit.

The Spark That Lit a Fire

The famous Jersey “greensand” was in relative abundance. Deposited and eroded by millions of years of geologic time from a period when New Jersey was underwater, the area was rich with the green mineral glauconite, whose eroded, sand-like remnants littered the landscape. It was here where Cope and Marsh began their joint dig to search for the next fossils.

Being previously underwater for millions of years, the dig site yielded a bunch of marine fossils for the two paleontologists and their teams, such as ancient turtles and crocodiles dating back to nearly 66 million years ago. Alongside these animals were pieces of dinosaur bone, as well as specimens of giant seafaring lizards called mosasaurs.

Being financially equipped, the two paleontologists didn’t really have to dig into the ground themselves; they could just pay off local miners to do the digging for them, then just send off the fossils to their respective offices depending on how good the fossils were. Of course, that’s exactly what Marsh did; while the two parted amicably from the dig site, seeing how good the fossils in Cope’s “home turf” were, Marsh secretly paid off the miners to send the fossils back to his collection in New Haven, Connecticut, instead of Cope’s back in Philadelphia. Naturally, this made Cope furious; how dare he go behind his back, at “his own backyard” too. This spark would start a bitter rivalry between the two, spanning nearly two decades.

Let’s Get Ready to Rumble

At this point, the “Bone Wars” were on. After the expedition, the two began humiliating each other in publications. Marsh pointed out (and correctly so, though the verification wouldn’t come until years after the statement was published) that Cope’s reconstruction of the plesiosaur Elasmosaurus was incorrect, with its head placed at the tip of what was actually it’s shorter tail instead of its longer neck. In retaliation, Cope began collecting fossils in Marsh’s “private bone-hunting turf” in Kansas and Wyoming, further souring their relationship.

In another spat, during a series of fossil digs out at the Western bone beds, the paleontologists were making great strides in discovering new species of ancient reptiles and mammals, including Uintatherium, Loxolophodon, and Eobasileus. Problem is, these finds were not completely determined to be fully unique from each other, meaning that some of their declared “finds” had actually already been found earlier by other paleontologists. What happened was that more of Marsh’s declared finds were determined unique, while Cope’s finds were not. At this point, Marsh declared that some of his new mammal finds were members of a new order of mammals that he coined Cinocerea. Cope, humiliated from their difference in finds, instead published a sweeping study where he proposed brand new classifications for mammals from the Eocene epoch; in it, he simply discarded Marsh’s earlier declared new order of mammals in favor of his own.

What is perhaps the most destructive clash of the two were during the famous Como Bluff expeditions. Como Bluff, a long ridge between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow in Wyoming, had been previously reported to house several potentially huge fossil finds. In fact, informants messaged Marsh about these finds; in response, Marsh paid off these informants—much to the dismay of the informants, as they felt they were “bullied” into the deal by Marsh, and the check Marsh sent couldn’t be cashed in due to Marsh using their letter pseudonyms instead of their real names—and sent his team to the area. Together with the informants, Marsh’s team found many iconic dinosaurs kids today would be all too familiar with: Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Allosaurus.

Despite Marsh’s efforts to quash news breaking out about the tantalizing fossil site, news spread quickly, reaching Cope. In fact, one of the disgruntled informants began working for Cope, bitter from his experience working under Marsh. This would spark the beginning of several summer expeditions to the area between teams working under the two paleontologists; sensational reports say these teams would sabotage each other’s finds, cover up their own dig sites after use to prevent the other from exploring the same site, and even destroyed small fossils in their wake to stop the other team from discovering something new. The fights between the two teams got ugly, and the paleontologists that funded them emptied their coffers in doing so.

The Aftermath

After years of back-and-forth bickering and public displays of resentment, the feud between Marsh and Cope bled the finances of the two dry, and dragged the entire field of paleontology at the time through the mud with them. In response, the two were socially isolated from their peers, with others wary of interacting with them due to their very public displays of anger. The feud got so bad that upon his death in 1897, Cope requested that his brain be preserved and weighed, confident even at death’s doorstep that he was better than Marsh. Marsh did not answer the challenge, dying 2 years later and simply being buried in a cemetery not far from his museum.

While the feud between the two got ugly, the very public race to find fossils sparked interest in future paleontologists, fueling further expeditions years after their deaths. Out of a desire to outcompete the other for finds, the two unearthed several of the world’s most famous dinosaurs, including the plate-backed Stegosaurus, the theropod Allosaurus, the long-necked Diplodocus, the small Coelophysis, and the famous three-horned Triceratops. Cope actually found two pieces of vertebra from a large dinosaur later on in 1892, and mistakenly believed them to be from a ceratopsid (like Triceratops); he named it Manospondylus gigas, derived from Greek for “giant porous vertebra.” It would take decades until another paleontologist, Henry Fairfield Osborn, would take another shot at examining Cope’s fossil vertebra and notice similarities between Cope’s find and a later find, concluding that M. gigas was actually a mislabeled specimen of another dinosaur—perhaps the most famous one: Tyrannosaurus rex.

Coelophysis bauri (St. John/Wikimedia Commons) Diplodocus carnegii (Anselmo/Carnegie Museum of Natural History/Wikimedia Commons) Triceratops prorsus (Caulfield/Los Angeles Museum of Natural History/Wikimedia Commons) Stegosaurus stenops (Maidment/Natural History Museum London/Wikimedia Commons) Allosaurus fragilis (San Diego Natural History Museum/Wikimedia Commons)

The “Bone Wars” between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh was bitter, and perhaps quite unnecessary, especially when compared to today’s age of cooperative learning and research. However, if not for the rivalry between the two, the field of paleontology would have been set back decades, and some of the world’s most famous dinosaurs and other ancient animals may not have been found at all. In a strange sense, we should perhaps feel thankful that there was a time when two intellectual men with money—and perhaps too much arrogance for their own good—decided that one going behind another’s back after a fateful trip to New Jersey was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Bibliography

- The Academy of Natural Science of Drexel University. (n.d.). Bone Wars: The Cope-Marsh Rivalry. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. Retrieved August 27, 2021, from https://ansp.org/exhibits/online-exhibits/stories/bone-wars-the-cope-marsh-rivalry/

- American Experience. (n.d.). O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope: A Rivalry. American Experience. Retrieved August 27, 2021, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/dinosaur-rivalry/

- Switek, B. (2020, March 22). The Bone Wars: how a bitter rivalry drove progress in palaeontology. Science Focus. Retrieved August 27, 2021, from https://www.sciencefocus.com/nature/the-bone-wars-how-a-bitter-rivalry-drove-progress-in-palaeontology/

- Wilford, J. N. (1999, November 7). The Fossil Wars. The New York Times.