At a Glance

- Spinosaurus, a massive sail-backed predator from Late Cretaceous North Africa, has long fascinated scientists due to its unusual anatomy, especially its debated aquatic adaptations and locomotion style.

- Initially discovered in Egypt in 1912 and destroyed in World War II, the holotype’s loss left paleontologists reliant on drawings and new fragmentary fossils that have sparked continuous reinterpretation of the species.

- Discoveries in the 2000s and 2010s suggested Spinosaurus had short hind limbs and a paddle-like tail, indicating potential aquatic behavior, though later studies questioned its ability to dive or swim effectively.

- Multiple studies, including recent ones from 2022 to 2024, suggest Spinosaurus may have been a shoreline predator with heron-like behavior, while others defend the aquatic hypothesis using tail structure and bone density.

- Debates also persist over its species identity, geographic range, and locomotion. Recent evidence supports a “graviportal biped” model and distinct African and South American spinosaurid lineages.

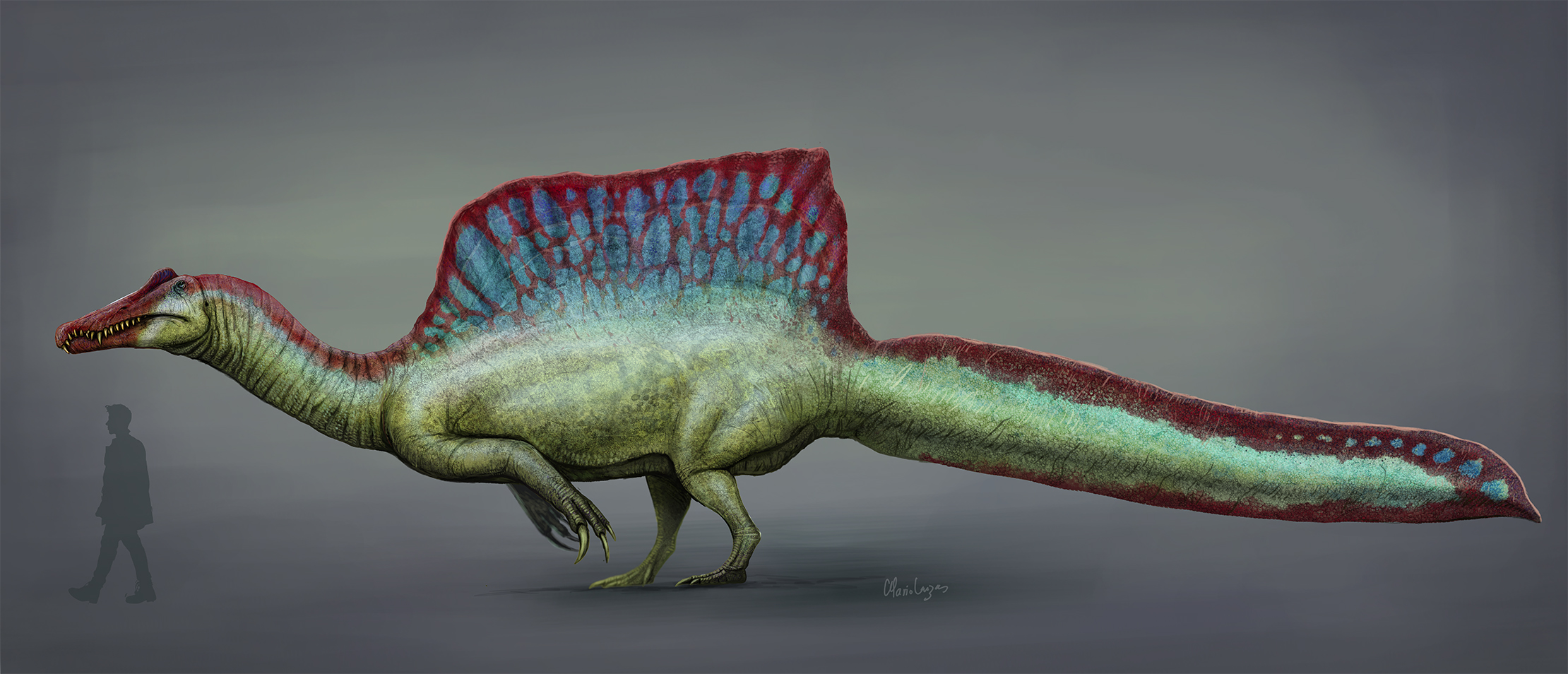

Few of the giant predatory dinosaurs that once roamed Earth have captivated scientists and the public, like Spinosaurus. This massive theropod—a group of typically bipedal (two-legged) carnivorous dinosaurs—often depicted with a striking sail on its back, was a formidable carnivore that lived in what is now North Africa during the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 100 to 94 million years ago. For decades, Spinosaurus has been a subject of intense scientific scrutiny, with its unique anatomy leading to continuous debates about its size, locomotion, and, most famously, its relationship with water. Even today, new research keeps challenging old assumptions, making Spinosaurus one of the most contentious and fascinating topics in paleontology.

A Fleeting Discovery

The story of Spinosaurus began in 1912 when Richard Markgraf discovered partial remains of a giant theropod in the Bahariya Formation of western Egypt. German paleontologist Ernst Stromer then described these initial findings in 1915 and formally named the new genus and species Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, meaning “Egyptian spine lizard.” The holotype, or the original specimen used to define the species, included parts of its lower jaw, teeth, various vertebrae (neck, trunk, and sacral), ribs, and gastralia (belly ribs). Crucially, it included nine “neural spines”—long extensions of the vertebrae that formed the distinctive sail-like structure on its back, with one reaching an impressive 1.65 meters (5.4 ft) in length. Stromer also designated other fragmentary remains, including vertebrae and hindlimb bones, as “Spinosaurus B” in 1934, considering them distinct enough to belong to another species, which later appeared to pertain to Carcharodontosaurus or Sigilmassasaurus.

Tragically, this invaluable original specimen was destroyed during a British bombing raid on Munich in April 1944, amidst World War II, which severely damaged the building housing the Paläontologisches Museum München. Fortunately, Stromer’s detailed drawings and specimen descriptions survived, providing the only concrete evidence of Spinosaurus for decades. This loss would significantly complicate future research, forcing paleontologists to piece together its anatomy from fragmentary discoveries. Early on, some even suggested Stromer’s original specimen might have been a “chimera” (a mix of bones from different animals), though this idea was later largely rejected.

A Dinosaur in Flux

The destruction of the holotype meant that Spinosaurus remained a shadowy figure for many years. Fragmentary new material came to light in the early 21st century, often sparking new controversies.

The Species Debate

One of the earliest debates centered on the existence of a second species. In 1996, Dale Russell described Spinosaurus maroccanus from Morocco based on differences in neck vertebrae. However, many researchers quickly considered S. maroccanus a nomen dubium (a dubious name), meaning its distinctness was uncertain or a junior synonym of S. aegyptiacus. The variability in individual vertebrae and the absence of the S. aegyptiacus holotype for direct comparison contributed to this uncertainty.

New Specimens and Drastic Reconstructions

New specimens fueled increasingly radical reconstructions. In 2005, a significant snout specimen (MSNM V4047) from the Kem Kem Beds of Morocco was described, which helped paleontologists estimate the Spinosaurus skull to be around 1.75 meters (5.7 ft) long. However, more recent estimates suggest a length of 1.6–1.68 meters (5.2–5.5 ft). This initially led to size estimates suggesting Spinosaurus could have been over 15 meters (49 ft) long, making it a contender for the largest known terrestrial carnivore, surpassing even Tyrannosaurus and Giganotosaurus.

A significant turning point came in 2014 with the description of FSAC-KK 11888, a partial subadult skeleton recovered from the Kem Kem Beds, a highly fossiliferous Early Cretaceous (around 100 million years old) riverine ecosystem in eastern Morocco. This specimen, controversially designated as a “neotype” (a new type specimen when the original is lost, though some researchers later rejected this designation), revealed unexpectedly short hind limbs. This finding led Nizar Ibrahim and his colleagues in 2014 to propose that Spinosaurus was poorly adapted for bipedal (two-legged) terrestrial locomotion and might have been an obligate quadruped (walking on four legs) on land, a stark contrast to how theropods are typically envisioned. This idea was met with immediate skepticism and criticism from other paleontologists, who questioned the scaling and integrity of the composite specimen.

The Paddle-Like Tail

Further revolutionary insights emerged in 2020 with the discovery and analysis of Spinosaurus‘s tail vertebrae by Ibrahim and colleagues. They revealed that its long, narrow tail was deepened by tall neural spines and elongated chevron bones, forming a flexible, paddle-like structure comparable to the tails of newts and crocodilians. Experiments showed this tail could generate significantly more thrust in water than the tails of land-dwelling theropods, suggesting Spinosaurus could swim effectively, akin to modern crocodilians. This led to the hypothesis that Spinosaurus had a lifestyle comparable to alligators, spending long periods in the water while hunting.

Bone Density Insights

In 2022, research by Matteo Fabbri and colleagues provided strong support for aquatic adaptation by analyzing bone density. They found that Spinosaurus had osteosclerosis (high bone density), similar to aquatic animals like penguins and manatees, which would have allowed it to control buoyancy for diving and pursuing prey underwater. This study involved comparing bone cross-sections from 250 species of extinct and living animals, establishing a strong correlation between dense bones and the ability to submerge foraging. Interestingly, they found that a close relative, Suchomimus, who lived by water and ate fish, had hollower bones, suggesting it was more of a wader than a submerged swimmer.

Diet and Sensory Adaptations

From its crocodilian-like skull with conical, unserrated teeth and raised nostrils, paleontologists have long suspected it was a piscivore (fish-eater). Direct evidence came from its relative, Baryonyx, whose stomach contained fish scales and bones. Scientists hypothesized that Spinosaurus used its snout’s pressure receptors to detect prey underwater, much like modern crocodiles. Bite force estimates suggest Spinosaurus had relatively weak bite forces compared to other theropods but were adapted for fast-snapping jaws to kill prey, a trait common in semi-aquatic feeders. Beyond fish, a 2024 paper suggests Spinosaurus and other spinosaurines also preyed upon small to medium-sized terrestrial vertebrates and even pterosaurs. Like a thresher shark’s, its long tail may also have been used to slap the water and stun fish.

Recent research in 2023 on the brains and inner ears of British spinosaurids, Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops, showed that their brains and sensory adaptations were surprisingly “nonspecialized” despite their unique ecology. Their olfactory bulbs (for smell) were not particularly developed, and their ears were attuned to low-frequency sounds. This suggests that the theropod ancestors of spinosaurs might have already possessed brains and sensory adaptations suited for part-time fish catching, meaning Spinosaurus primarily needed to evolve its unusual snout and teeth for its specialized diet. These insights were gained through advanced CT-based imaging of fossils.

Spinosaurid Origins

The discovery of Protathlitis cinctorrensis, a new spinosaurid species from Spain dating back to the Early Cretaceous (127-126 million years ago), has shed light on the broader evolutionary history of spinosaurids. This finding supports the hypothesis that spinosaurids may have originated in Europe (specifically Laurasia, a large landmass in the northern hemisphere) and then migrated to Africa and Asia, where they diversified. In Europe, baryonychines like Protathlitis were dominant, while in Africa, spinosaurines like Spinosaurus became most abundant.

A Bunch of Lingering Mysteries

The journey of Spinosaurus from a vague, sail-backed theropod to a highly specialized, semi-aquatic predator has been a rollercoaster of discovery and reinterpretation. However, as new evidence emerges, so do new questions and controversies.

The Great Aquatic Debate

The most heated debate continues to be about Spinosaurus‘s primary aquatic lifestyle. While the paddle-like tail and bone density strongly suggest active swimming and submersion, these findings have faced significant challenges.

- In 2018, Donald Henderson argued that Spinosaurus‘s lung placement and buoyancy would have made it unable to sink or dive, suggesting it needed to paddle its hind legs to stay upright in water constantly. He theorized it likely spent most of its time on land or in shallow water.

- David Hone and Thomas Holtz further argued in 2021 that Spinosaurus‘s anatomy, including its ventrally positioned nostrils (requiring the whole head to be lifted to breathe), seemingly rigid trunk, and scarcely muscled tail, was poorly suited for active aquatic pursuit, suggesting a more shoreline generalist lifestyle.

- Adding to the complexity, a 2022 study by Paul Sereno and his colleagues, creating digital skeletons and flesh models, found that Spinosaurus and Suchomimus would have been unstable when swimming at the surface and too buoyant to dive and fully submerge. They also suggested that Spinosaurus was wholly bipedal on land and a slow-moving surface swimmer, proposing its large tail fin was more for display than primary swimming.

- Most recently, in 2024, Nathan Myhrvold and colleagues re-evaluated the bone density study, highlighting significant statistical issues that “undermine the conclusions.” They contended that Spinosaurus was not a diving pursuit predator, suggesting it hunted more like herons, wading and plucking prey from the water. They explained that dense bone in Spinosaurus could be due to needing extra bone strength to support its weight on its relatively short hind limbs, rather than indicating buoyancy control for diving. Another 2024 paper analyzing Spinosaurus‘s skull morphology also concluded that its hunting method would likely be most similar to wading birds.

Locomotion on Land

The debate over Spinosaurus‘s terrestrial locomotion continues to evolve. While the 2014 partial skeleton (FSAC-KK 11888) led to the idea of an obligate quadruped, this has mainly been walked back.

- Henderson’s 2018 analysis suggested that Spinosaurus was competent at bipedal locomotion, with its center of mass allowing it to stand upright.

- Most recently, in a 2024 article, Sereno and his colleagues, who had earlier supported quadrupedality, rectified their calculations. They now state that Spinosaurus fits the criteria of a graviportal biped, meaning a slow-moving, two-legged animal rather than an obligate quadruped. This shows the ongoing dynamic nature of Spinosaurus research.

Taxonomic Identity and Geographic Range

The exact number of Spinosaurus species and the relationships among North African spinosaurids remain contentious.

- Some scientists continue to consider the genus Sigilmassasaurus, another spinosaurid from North Africa, a junior synonym of Spinosaurus. However, a 2015 re-description disputed this, considering Sigilmassasaurus valid. In 2024, a complete posterior cervical vertebra was assigned to Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis, implying it is still considered distinct by some researchers.

- The Brazilian spinosaurid Oxalaia is also a subject of debate. While a 2020 paper proposed it as a potential junior synonym of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, implying a broader geographic distribution and faunal exchange between South America and Africa, later studies in 2021 and 2023 rejected this synonymy, pointing to distinct skull features of Oxalaia. The status of Oxalaia is further complicated by the 2018 National Museum of Brazil fire, though badly damaged remains have been recovered, and a publication is in preparation for 2025.

The ongoing debates highlight the challenging nature of paleontological research, where scientists must piece together the lives of extinct animals from incomplete fossil records. Each new bone, each new analysis, reshapes our understanding of this magnificent creature. As new technologies like CT-based imaging and advanced statistical methods allow for more detailed examination of fossil fragments and biomechanical modeling, the true nature of Spinosaurus continues to emerge, cementing its place as one of the most dynamic and debated dinosaurs in the history of science.

References

- Amiot, R., Buffetaut, E., Lécuyer, C., Wang, X., Boudad, L., Ding, Z., Fourel, F., Hutt, S., Martineau, F., Medeiros, M. A., Mo, J., Simon, L., Suteethorn, V., Sweetman, S., Tong, H., Zhang, F., & Zhou, Z. (2010). Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods. Geology, 38(2), 139–142. https://doi.org/10.1130/G30402.1

- Arden, T. M. S., Klein, C. G., Zouhri, S., & Longrich, N. R. (2019). Aquatic adaptation in the skull of carnivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) and the evolution of aquatic habits in spinosaurids. Cretaceous Research, 93, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2018.06.013

- Buffetaut, E., Martill, D., & Escuillié, F. (2004). Pterosaurs as part of a spinosaur diet. Nature, 430(6995), 33–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/430033a

- Cuff, A. R., & Rayfield, E. J. (2013). Feeding mechanics in spinosaurid theropods and extant crocodilians. PLoS ONE, 8(5), e65295. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065295

- D’Amore, D. C., Johnson‐Ransom, E., Snively, E., & Hone, D. W. E. (2025). Prey size and ecological separation in spinosaurid theropods based on heterodonty and rostrum shape. The Anatomical Record, 308(5), 1331–1348. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25563

- Evers, S. W., Rauhut, O. W. M., Milner, A. C., McFeeters, B., & Allain, R. (2015). A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur Sigilmassasaurus from the “middle” Cretaceous of Morocco. PeerJ, 3, e1323. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1323

- Fabbri, M., Navalón, G., Benson, R. B. J., Pol, D., O’Connor, J., Bhullar, B.-A. S., Erickson, G. M., Norell, M. A., Orkney, A., Lamanna, M. C., Zouhri, S., Becker, J., Emke, A., Dal Sasso, C., Bindellini, G., Maganuco, S., Auditore, M., & Ibrahim, N. (2022). Subaqueous foraging among carnivorous dinosaurs. Nature, 603(7903), 852–857. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04528-0

- Glut, D. F. (1982). The new dinosaur dictionary (1. ed). Citadel Press.

- Henderson, D. M. (2018). A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PeerJ, 6, e5409. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5409

- Hone, D., & Holtz, T. (2021). Evaluating the ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline generalist or aquatic pursuit specialist? Palaeontologia Electronica. https://doi.org/10.26879/1110

- Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P. C., Varricchio, D. J., Martill, D. M., Dutheil, D. B., Unwin, D. M., Baidder, L., Larsson, H. C. E., Zouhri, S., & Kaoukaya, A. (2020). Geology and paleontology of the upper cretaceous kem kem group of eastern morocco. ZooKeys, 928, 1–216. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.928.47517

- Isasmendi, E., Navarro-Lorbés, P., Sáez-Benito, P., Viera, L. I., Torices, A., & Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (2023). New contributions to the skull anatomy of spinosaurid theropods: Baryonychinae maxilla from the Early Cretaceous of Igea (La rioja, spain). Historical Biology, 35(6), 909–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2022.2069019

- Lacerda, M. B. S., Grillo, O. N., & Romano, P. S. R. (2022). Rostral morphology of Spinosauridae (Theropoda, megalosauroidea): Premaxilla shape variation and a new phylogenetic inference. Historical Biology, 34(11), 2089–2109. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2021.2000974

- Lakin, R. J., & Longrich, N. R. (2019). Juvenile spinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) from the middle Cretaceous of Morocco and implications for spinosaur ecology. Cretaceous Research, 93, 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2018.09.012

- Mahler, L. (2005). Record of abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the cenomanian of morocco. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 25(1), 236–239. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0236:ROADTF]2.0.CO;2

- Molina-Pérez, R., Larramendi, A., Atuchin, A., & Mazzei, S. (2016). Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios: Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos. Larousse.

- Myhrvold, N. P., Baumgart, S. L., Vidal, D., Fish, F. E., Henderson, D. M., Saitta, E. T., & Sereno, P. C. (2024). Diving dinosaurs? Caveats on the use of bone compactness and pFDA for inferring lifestyle. PLOS ONE, 19(3), e0298957. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298957

- Paul, G. S. (1988). Predatory dinosaurs of the world: A complete illustrated guide. Simon and Schuster.

- Rauhut, O. W. M. (Palaeontological Association). (2003). The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Palaeontological Association.

- Sakamoto, M. (2022). Estimating bite force in extinct dinosaurs using phylogenetically predicted physiological cross-sectional areas of jaw adductor muscles. PeerJ, 10, e13731. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13731

- Sasso, C. D., Maganuco, S., Buffetaut, E., & Mendez, M. A. (2005). New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus , with remarks on its size and affinities. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 25(4), 888–896. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2

- Sereno, P. C., Beck, A. L., Dutheil, D. B., Gado, B., Larsson, H. C. E., Lyon, G. H., Marcot, J. D., Rauhut, O. W. M., Sadleir, R. W., Sidor, C. A., Varricchio, D. D., Wilson, G. P., & Wilson, J. A. (1998). A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from africa and the evolution of spinosaurids. Science, 282(5392), 1298–1302. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5392.1298

- Sereno, P. C., Myhrvold, N., Henderson, D. M., Fish, F. E., Vidal, D., Baumgart, S. L., Keillor, T. M., Formoso, K. K., & Conroy, L. L. (2022). Spinosaurus is not an aquatic dinosaur. eLife, 11, e80092. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80092

- Smart, S., & Sakamoto, M. (2024). Using linear measurements to diagnose the ecological habitat of Spinosaurus. PeerJ, 12, e17544. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17544

- Smith, J. B., Lamanna, M. C., Mayr, H., & Lacovara, K. J. (2006). New information regarding the holotype of spinosaurus aegyptiacus stromer, 1915. Journal of Paleontology, 80(2), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2006)080[0400:NIRTHO]2.0.CO;2

- Smyth, R. S. H., Ibrahim, N., & Martill, D. M. (2020). Sigilmassasaurus is Spinosaurus: A reappraisal of African spinosaurines. Cretaceous Research, 114, 104520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104520

- Stromer, E. (1927). II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharîje-Stufe (Unterstes cenoman)9. Die Plagiostomen, mit einem Anhang über käno- und mesozoische Rückenflossenstacheln von Elasmobranchiern. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783486755473

- Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (Eds.). (2004). The dinosauria (2nd ed). University of California Press.