Hero image: © The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Ill. Mattias Karlén

At a Glance

- The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Mary Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance.

- Shimon Sakaguchi identified a specific subset of immune cells, now called regulatory T cells, that actively suppress the immune system and prevent it from attacking the body’s own tissues.

- Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell discovered the master regulator gene Foxp3 by studying mice with a severe autoimmune disorder, linking a single gene to immune system control.

- The laureates’ work connected these findings, demonstrating that the FOXP3 gene is crucial for the development and function of regulatory T cells, which maintain immune self-tolerance.

- These fundamental discoveries have opened new avenues for treating autoimmune diseases and cancer by modulating the activity of these crucial regulatory T cells in patients worldwide.

Three scientists have won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their foundational discoveries of how the immune system is prevented from attacking the body’s own tissues. The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet announced last October 7th that the prize will be shared equally by Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their work in identifying regulatory T cells and the master gene that controls them, launching a new era in immunology and medicine.

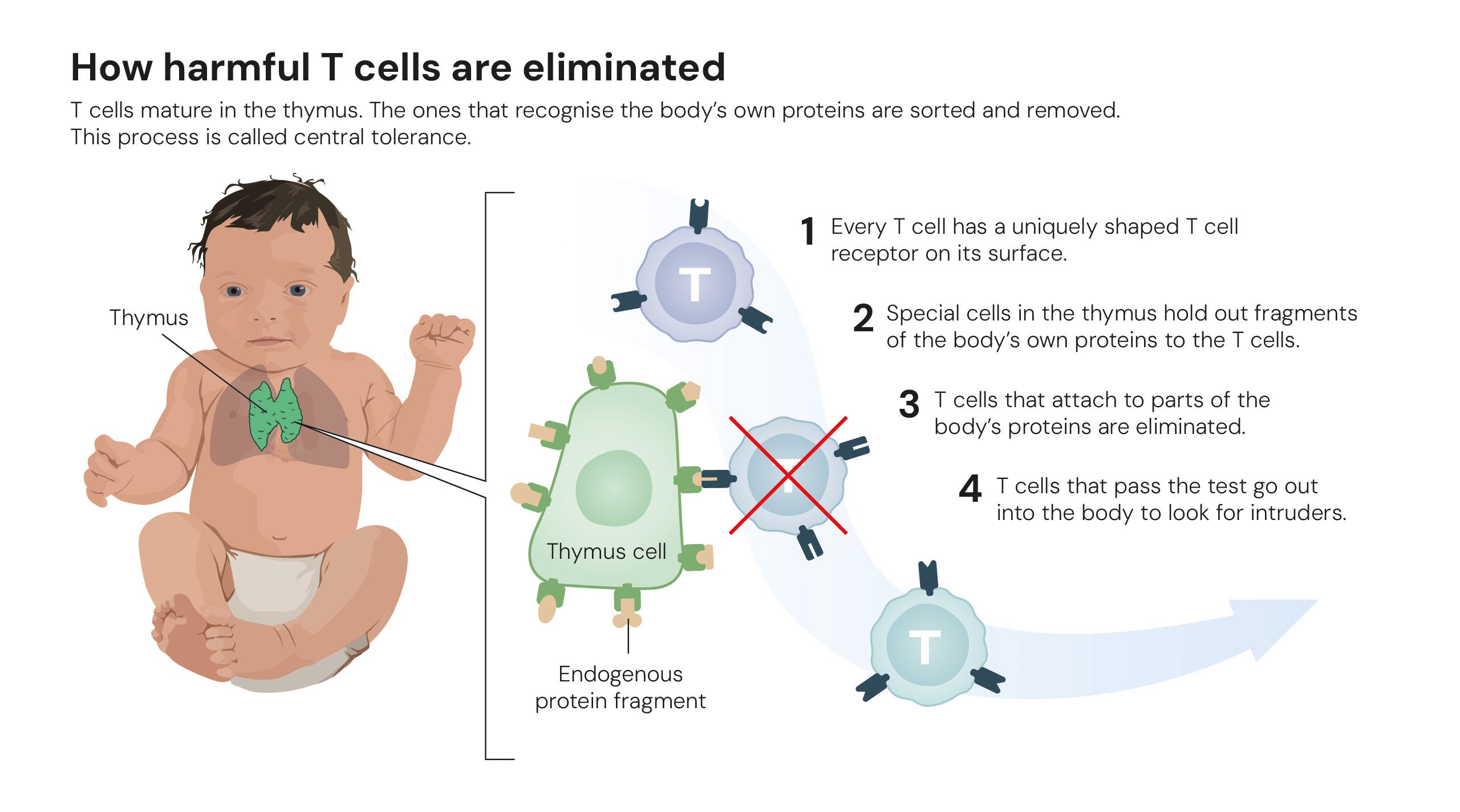

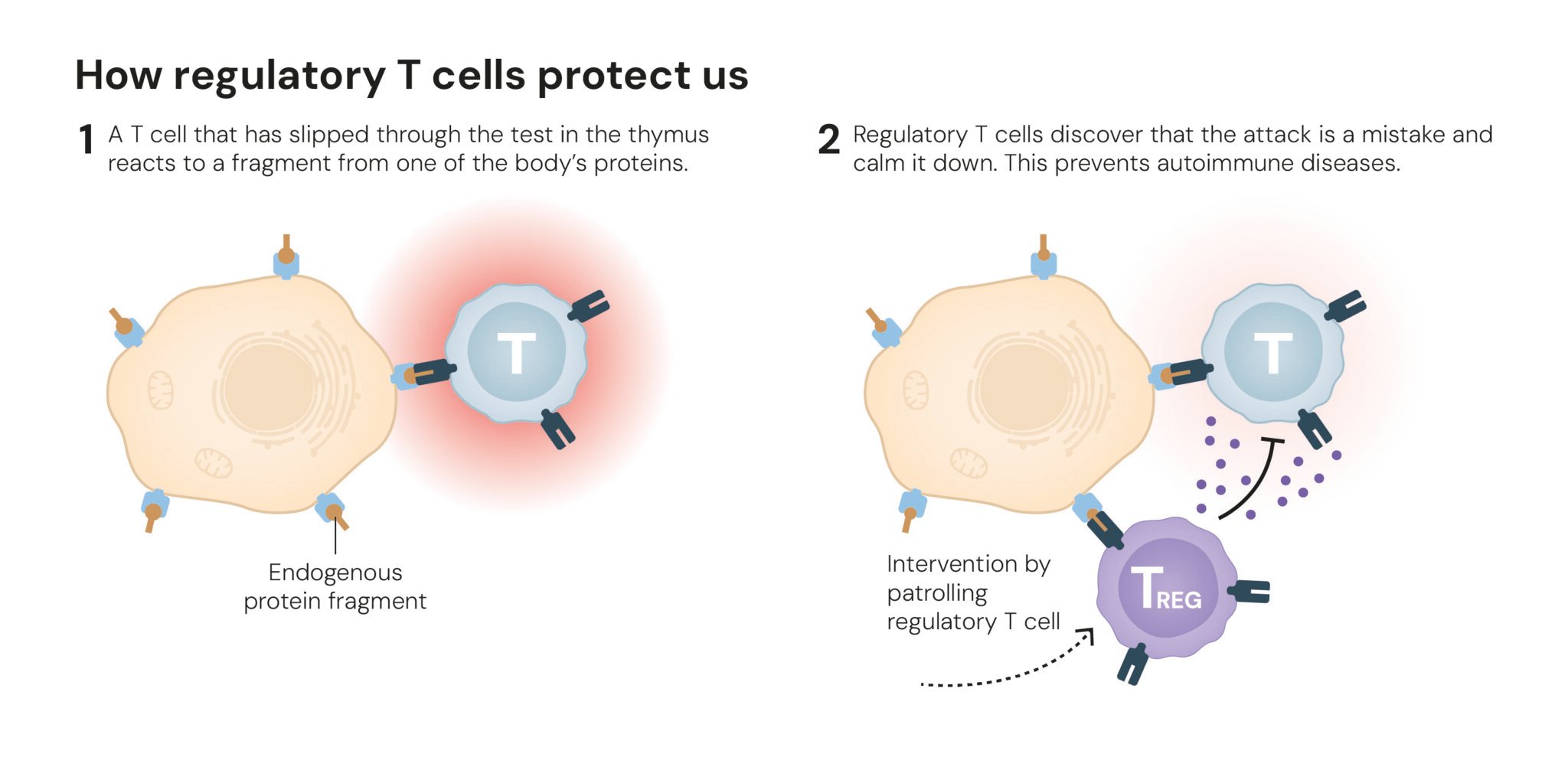

For decades, scientists understood that the immune system learns to tolerate the body’s own cells through a process in the thymus called central tolerance, where self-reactive immune cells are eliminated. However, this system isn’t perfect, and the question of how the body handles the cells that escape this initial screening remained a significant puzzle. An earlier theory of “suppressor T cells” from the 1970s was abandoned mainly due to inconsistent results, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of immune regulation. This is where the laureates’ work provided a definitive answer.

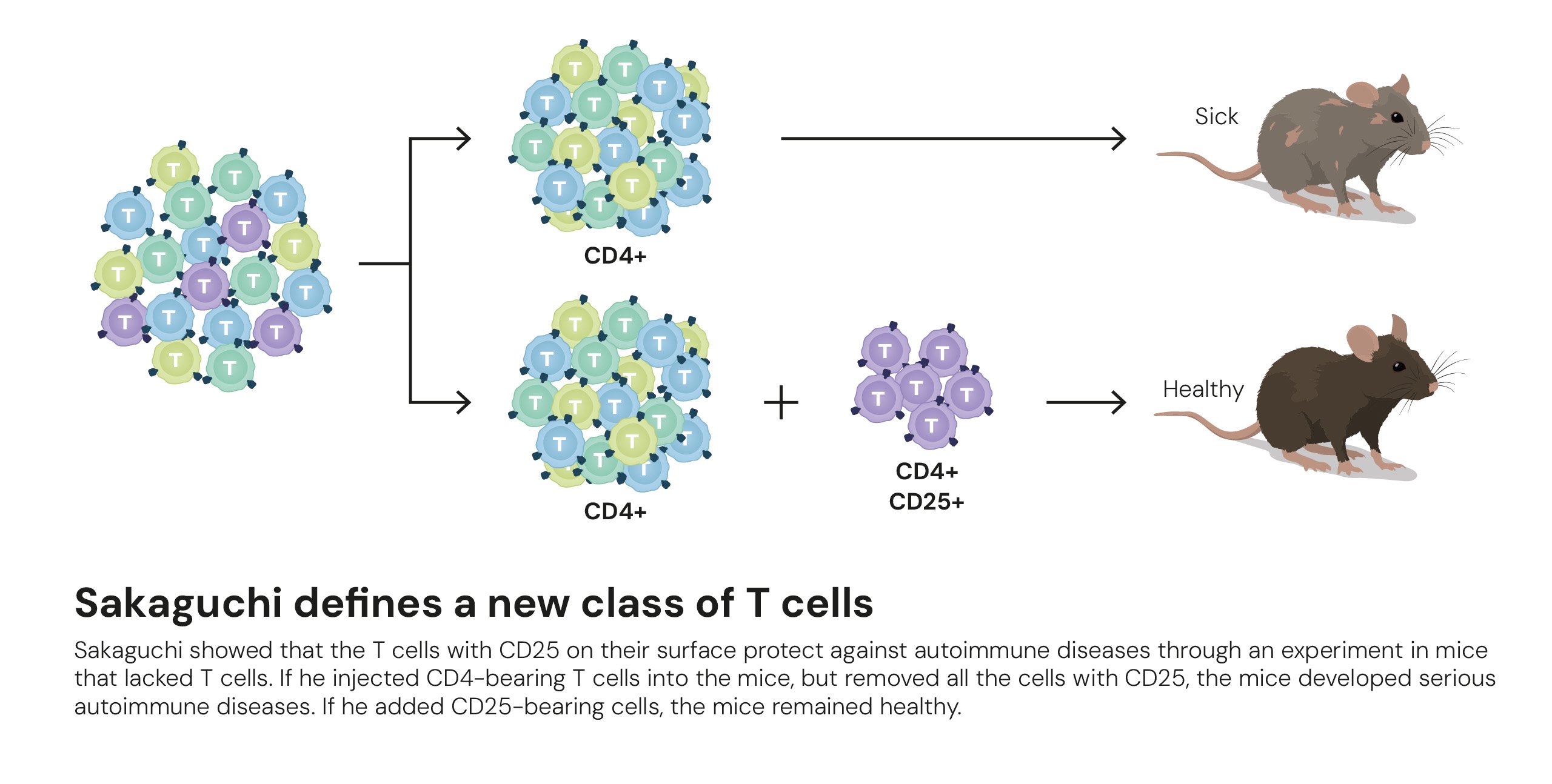

The first breakthrough came from Shimon Sakaguchi. In a landmark 1995 paper published in the Journal of Immunology, he demonstrated the existence of a specialized group of immune cells that actively police the immune system. Working with mice, he showed that a specific subset of T cells, identifiable by the surface markers CD4 and CD25, could prevent the development of autoimmune diseases. When these CD4+CD25+ cells were removed, the immune system ran rampant, but when they were reintroduced, tolerance was restored. These cells were later named regulatory T cells, or Tregs.

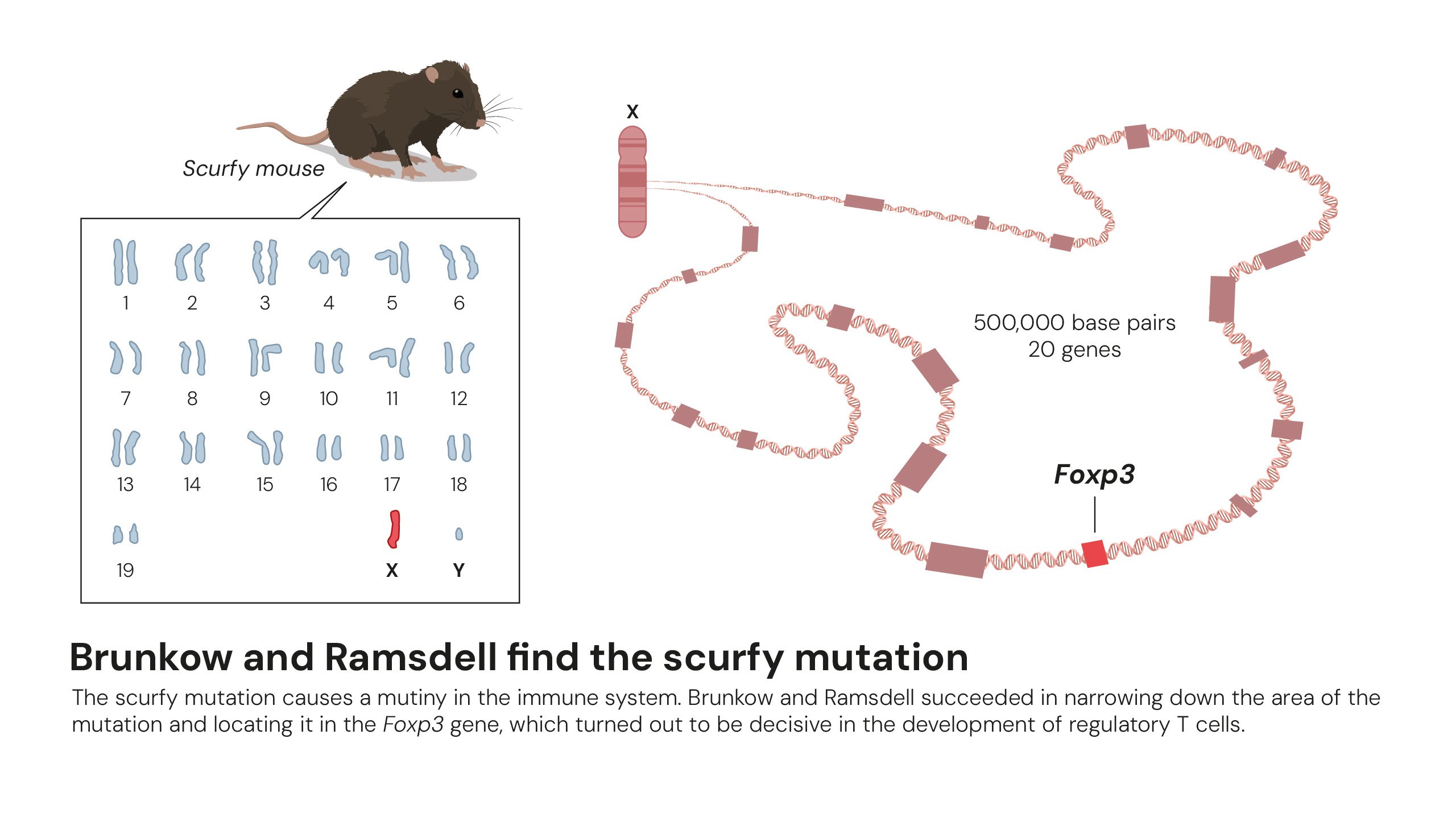

Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell uncovered the second critical piece of the puzzle. In 2001, they published their findings in Nature Genetics after studying a strain of mice called “scurfy,” which suffered from a fatal autoimmune disorder. Through years of meticulous genetic mapping, they identified a single mutated gene responsible for the disease, which they named Foxp3. They soon confirmed that mutations in the human version of this gene, FOXP3, caused a rare but severe autoimmune condition in young boys known as IPEX syndrome.

These two parallel discoveries converged to revolutionize the field of immunology. Sakaguchi’s team quickly showed that the FOXP3 gene was the “master switch” for the regulatory T cells he had discovered, governing their development and function. Without a working FOXP3 gene, the body cannot produce these critical immune guardians. “Their discoveries have been decisive for our understanding of how the immune system functions and why we do not all develop serious autoimmune diseases,” said Olle Kämpe, chair of the Nobel Committee, in a press release.

The identification of Tregs and FOXP3 has since transformed medicine, opening new therapeutic avenues for a wide range of conditions. Researchers are now developing treatments to enhance Treg activity and combat autoimmune diseases, as well as prevent organ transplant rejection. Conversely, in cancer treatment, therapies are being tested to inhibit Tregs within tumors, dismantling the protective barrier they form and allowing the immune system to attack cancer cells. Several of these innovative treatments are currently undergoing clinical trials, promising to turn these fundamental discoveries into life-saving therapies.

References

- Brunkow, M. E., Jeffery, E. W., Hjerrild, K. A., Paeper, B., Clark, L. B., Yasayko, S.-A., Wilkinson, J. E., Galas, D., Ziegler, S. F., & Ramsdell, F. (2001). Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nature Genetics, 27(1), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/83784

- Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. (2025a, October 7). Nobel prize in physiology or medicine 2025. NobelPrize.Org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2025/press-release/

- Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. (2025b, October 7). Nobel prize in physiology or medicine 2025. NobelPrize.Org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2025/popular-information/

- Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. (2025c, October 7). Scientific background 2025: Immune tolerance—The identification of regulatory T cells and FOXP3. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/advanced-medicineprize2025.pdf

- Sakaguchi, S., Sakaguchi, N., Asano, M., Itoh, M., & Toda, M. (1995). Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (Cd25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. The Journal of Immunology, 155(3), 1151–1164. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.155.3.1151