Hero image: ©Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

At a Glance

- Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar Yaghi won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their development of highly porous materials called metal-organic frameworks.

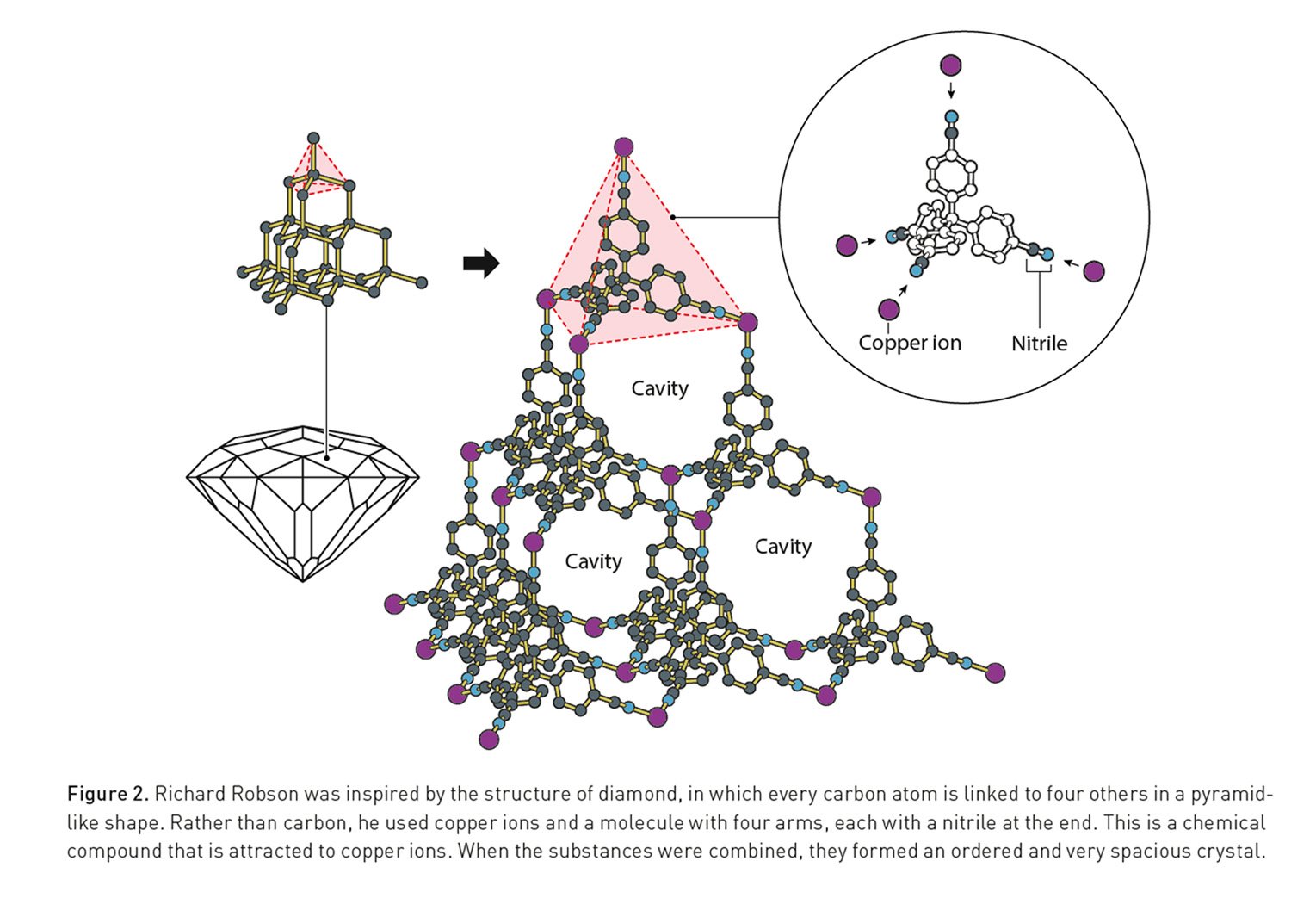

- Richard Robson first conceived the idea in 1989, demonstrating that metal ions and organic linkers could form predictable, spacious crystals resembling a diamond-like lattice.

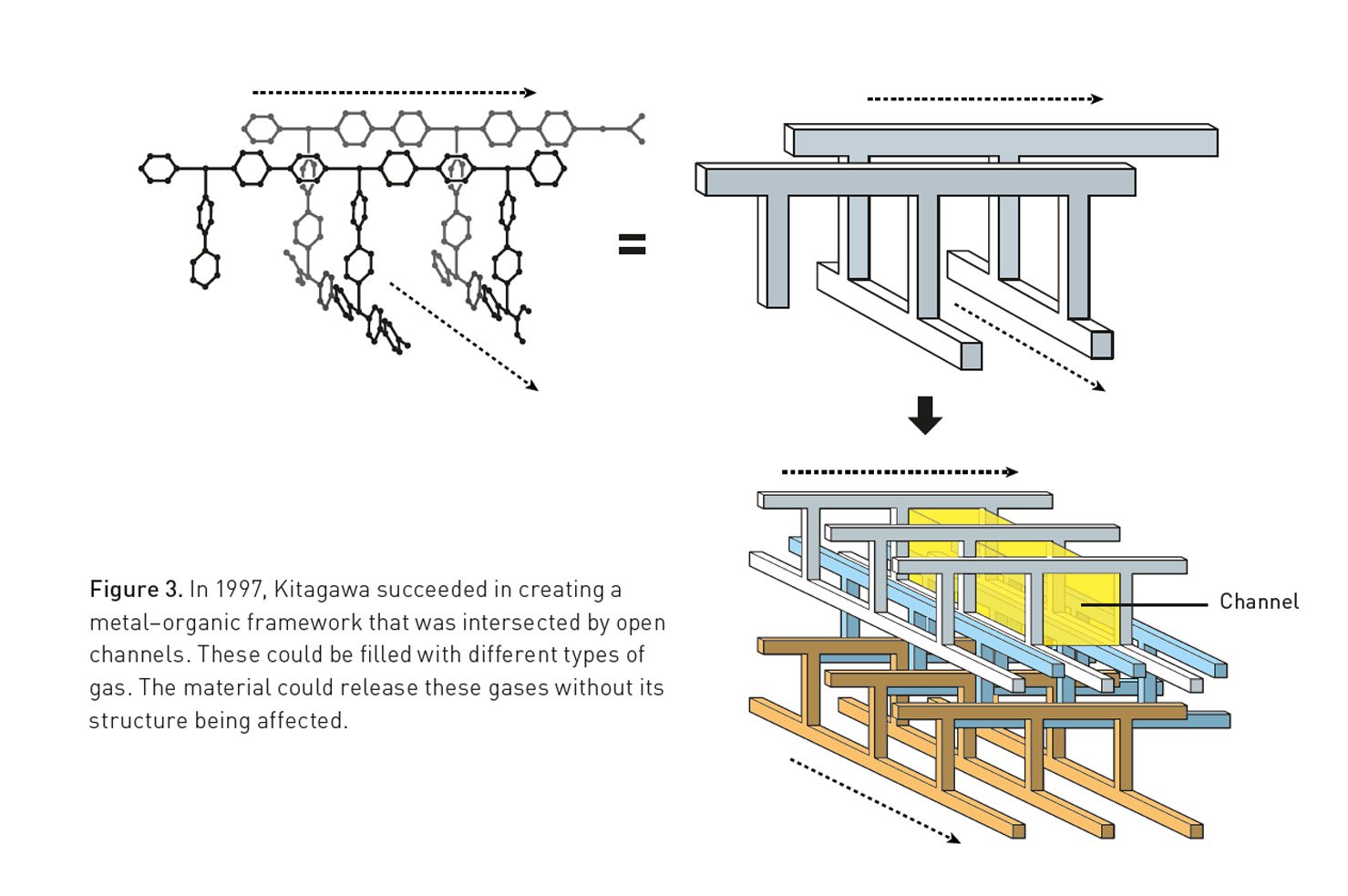

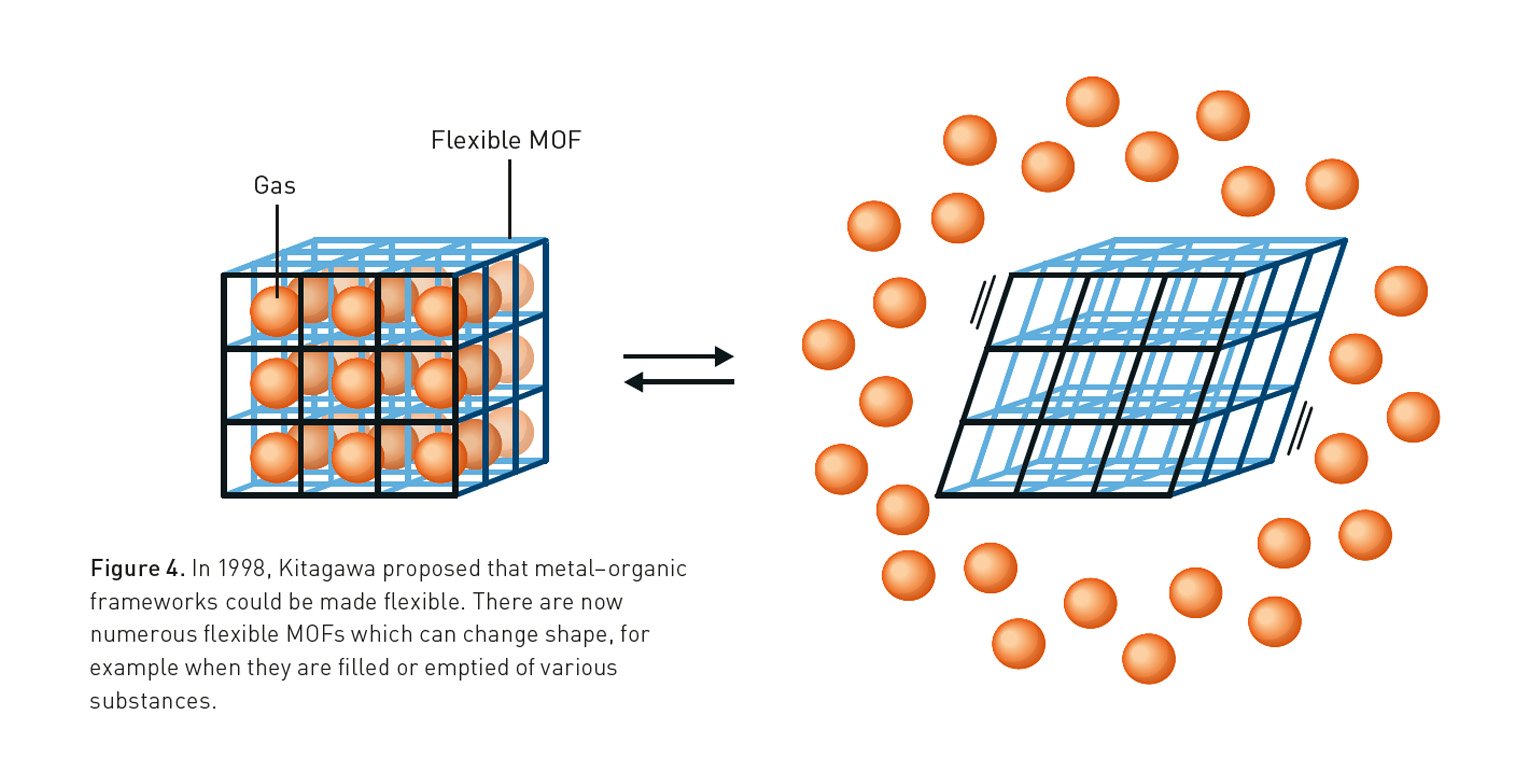

- Susumu Kitagawa created the first stable MOFs that could absorb and release gases without collapsing and introduced the concept that these materials could be flexible.

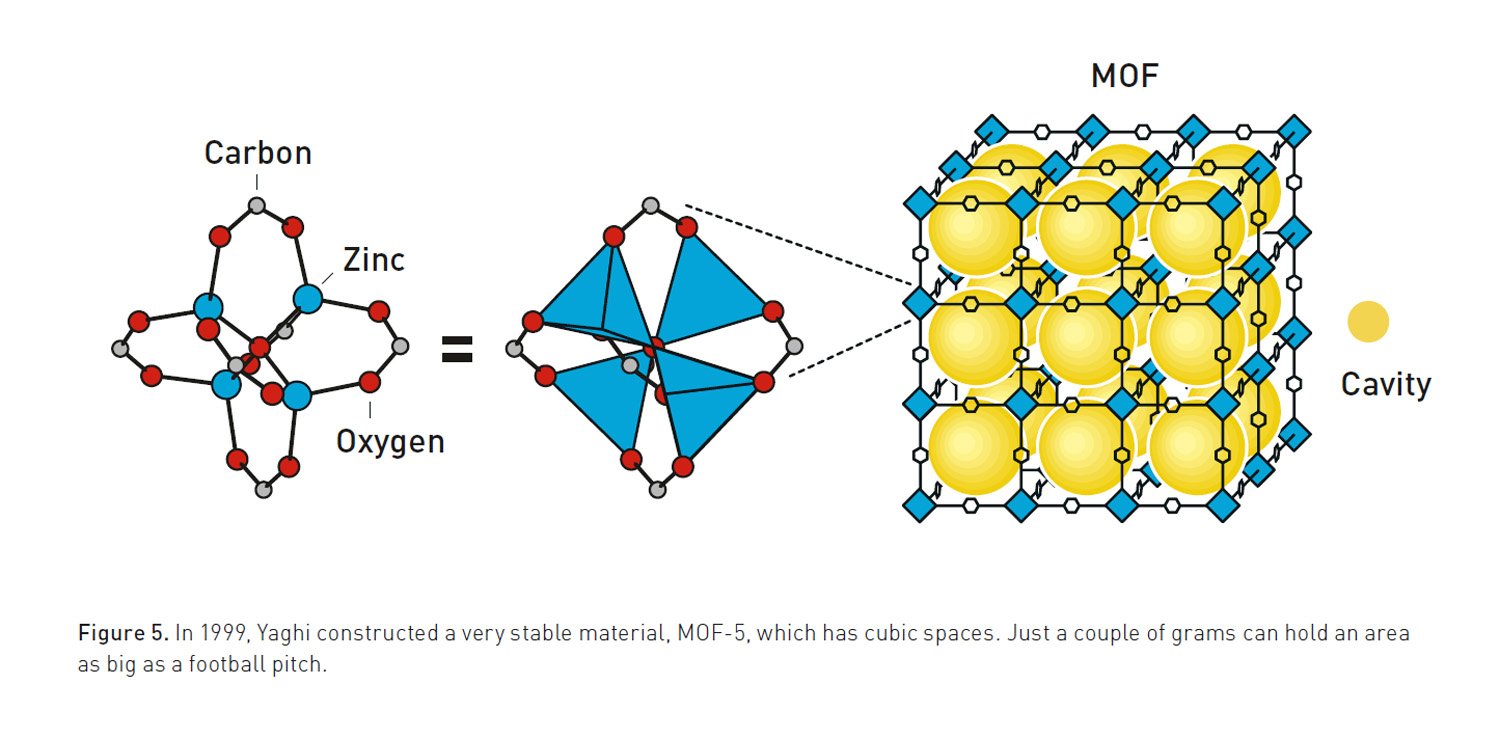

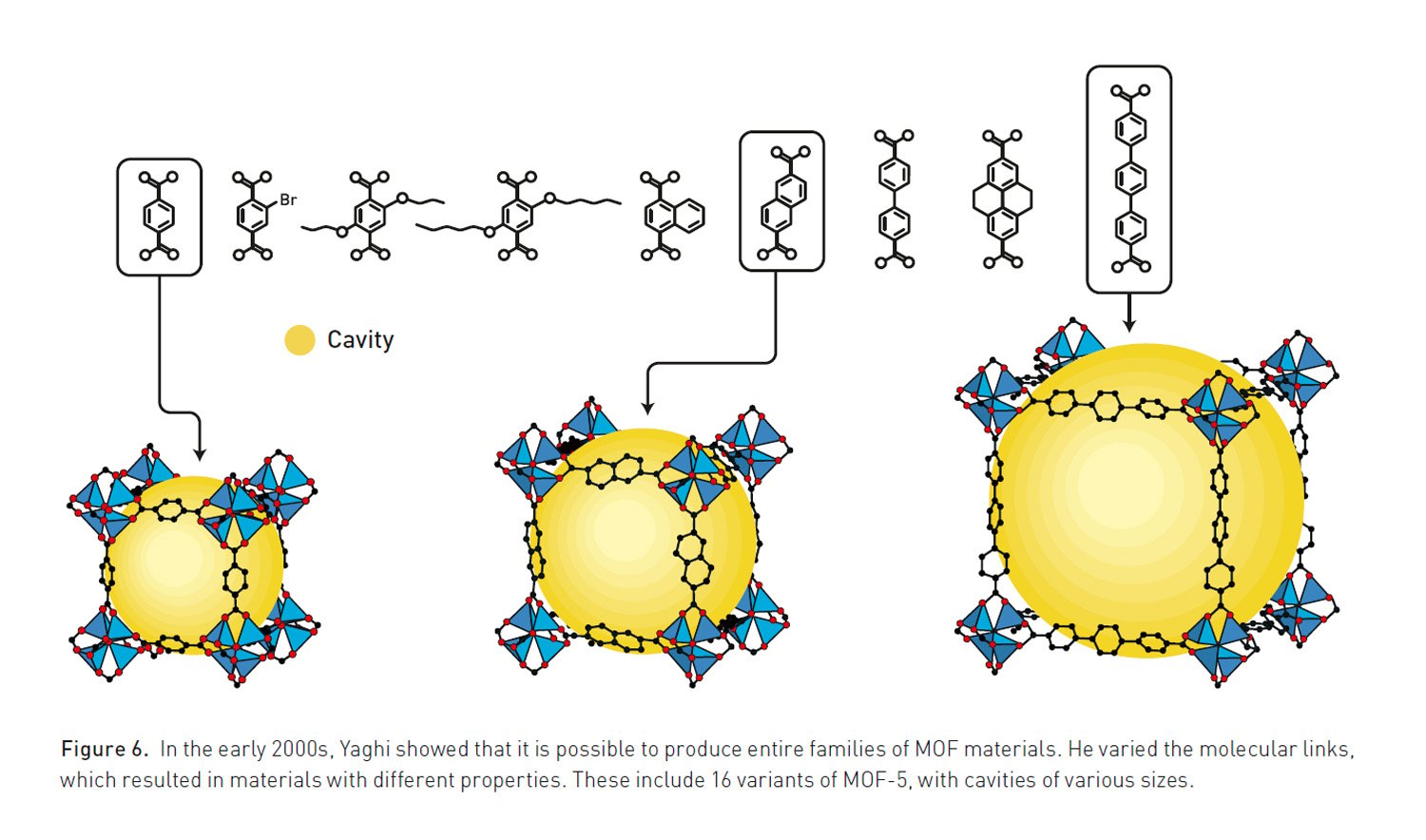

- Omar Yaghi coined the term “metal-organic framework,” created the exceptionally stable MOF-5, and established “reticular chemistry” as a method for rationally designing new materials.

- These versatile frameworks have numerous potential applications, including capturing carbon dioxide, harvesting water from the air, removing pollutants, and storing hydrogen for fuel.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University, Richard Robson of the University of Melbourne, and Omar M. Yaghi of the University of California, Berkeley, “for the development of metal-organic frameworks.” These three scientists pioneered a new form of molecular construction, creating highly porous, crystalline materials with vast internal spaces. Known as metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, these structures function like molecular sponges, capable of capturing specific gases, harvesting water from desert air, and catalyzing chemical reactions, offering potential solutions to some of humanity’s most pressing challenges.

The journey began in 1989 when Richard Robson, inspired by simple ball-and-stick models used for teaching, envisioned a new way to build materials. In a paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, he described combining positively charged copper ions with a four-armed organic molecule. The components self-assembled into a highly ordered, spacious crystal akin to a diamond framework filled with countless cavities. While Robson’s initial structures were unstable and prone to collapse, his work demonstrated that molecules could be precisely arranged into predictable, porous networks, laying the conceptual foundation for the entire field.

Building on this pioneering vision, Susumu Kitagawa provided the field with stability and function. In a significant 1997 breakthrough, his research group created a three-dimensional MOF using cobalt ions that remained stable even after the solvent inside was removed. He demonstrated that gases like methane and nitrogen could flow into and out of the structure without causing it to collapse. Kitagawa also introduced the revolutionary concept that MOFs could be flexible. In a 1998 article in the Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, he proposed that these “soft porous crystals” could change their shape in response to guest molecules, behaving like molecular lungs.

At the same time, Omar M. Yaghi was developing methods for more controlled and predictable synthesis. In a 1995 Nature article, he coined the term “metal-organic framework” to describe these materials. His work culminated in the 1999 creation of MOF-5, an exceptionally stable and spacious framework that became a classic in the field. MOF-5 possesses an enormous internal surface area—just a few grams of the material contains the area of a football pitch. Yaghi later introduced the concept of “reticular chemistry” in the journal Science, establishing a method for rationally designing MOFs with tailored properties by systematically changing their building blocks.

Metal-organic frameworks are constructed from two primary components: metal ions or clusters that act as “corners” or nodes, and carbon-based organic molecules that serve as “linkers” connecting these nodes. This modular, Lego-like approach allows chemists to design MOFs with specific pore sizes, shapes, and chemical functionalities. Unlike zeolites, which are rigid, silicon-based porous materials, MOFs can be created from a nearly infinite combination of building blocks, making them highly tunable for various tasks and even enabling the creation of flexible, dynamic structures.

Following the laureates’ foundational discoveries, researchers have designed tens of thousands of unique MOFs with a wide array of applications. Some are being developed to capture carbon dioxide from industrial emissions, while others can pull potable water from arid air. Their ability to selectively absorb molecules makes them promising candidates for separating pollutants like PFAS from water, storing hydrogen for clean energy vehicles, and safely containing toxic industrial gases. “Metal-organic frameworks have enormous potential, bringing previously unforeseen opportunities for custom-made materials with new functions,” said Heiner Linke, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, in a press release.

References

- Hoskins, B. F., & Robson, R. (1989). Infinite polymeric frameworks consisting of three dimensionally linked rod-like segments. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 111(15), 5962–5964. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00197a079

- Kitagawa, S., & Kondo, M. (1998). Functional micropore chemistry of crystalline metal complex-assembled compounds. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 71(8), 1739–1753. https://doi.org/10.1246/bcsj.71.1739

- Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. (2025a, October 8). Nobel prize in chemistry 2025. NobelPrize.Org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/press-release/

- Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. (2025b, October 8). Nobel prize in chemistry 2025. NobelPrize.Org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/popular-information/

- Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. (2025c, October 8). Scientific Background to the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025: Metal-Organic Frameworks. The Nobel Committee for Chemistry. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/advanced-chemistryprize2025.pdf

- Yaghi, O. M., Li, G., & Li, H. (1995). Selective binding and removal of guests in a microporous metal–organic framework. Nature, 378(6558), 703–706. https://doi.org/10.1038/378703a0