Parks, small woodlands and even simple patches of grass not only keep a city attractive, but also help people find a sense of bliss in an otherwise bustling urban environment. With new technologies, we can plan and monitor these urban “green spaces” better than ever before.

As several studies have highlighted, nature within urban settings plays a pivotal role in combating many of the global public health challenges commonly associated with urbanisation. This includes maladies such as depression and high blood pressure. A 2022 study showed that trees actually have the ability to improve urban air quality as leaves and pine needles capture pollutants from the air.

That cities do need green spaces is therefore not a particularly contentious issue. It is, however, an open question as to how much green space a city ought to have. Even here, science can provide some guidelines, as research points to at least 9 square metres of green space per individual, with an ideal value of 50 square metres per capita in a city (for comparison, an average UK car parking space takes up about 12 square metres).

Green landscaping

The big question is therefore what kind of green space do we want? A well-kept but human-made park? Or something more natural and unkempt, such as groves, meadows or field-like areas? As we discuss in our forthcoming book, Designing Smart and Resilient Cities for a Post-Pandemic World: Metropandemic Revolution, this is largely contingent on the geographic preconditions of the city in question. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a diversity of different kinds of green areas if possible, yet it is an inescapable fact that some cities are blessed with lush vegetation while others are not.

However, all is not lost for cities without much natural green area, as such environments can be constructed in urban settings that have previously been bereft of naturally growing trees and grass. This “green landscaping” can be undertaken even in areas that would otherwise seem unlikely. One prime example is the High Line in New York City, a 1.45 mile (2.33km) long elevated linear park built on an abandoned railway viaduct. Since it opened in stages about a decade ago, the High Line has become an exemplar of green landscape redesign that seeks to turn obsolete infrastructure into green, vibrant public spaces.

While it is known that greenery has positive effects on mankind at large, it is more difficult to prove the exact causal relationship in exactly how green areas affect our health. In this regard, digital technology can be an essential tool for urban planners to determine where green landscape redesign is best employed.

Smart technology

One concept that is seeing particularly rapid development is “smart urban forests”, which refers to using tree monitors, 3D-imagery and other internet of things-linked technologies to help manage the forest. This “internet of nature” could monitor soil health, measure air pollution or ensure urban forests are adequately hydrated.

Future technology could also enable the use of open data platforms and more public engagement. Planners could collect various perspectives from the general population using an app, for instance, while also using digital technology to map and boost urban biodiversity and to ensure that green areas are placed where they will achieve maximum efficiency.

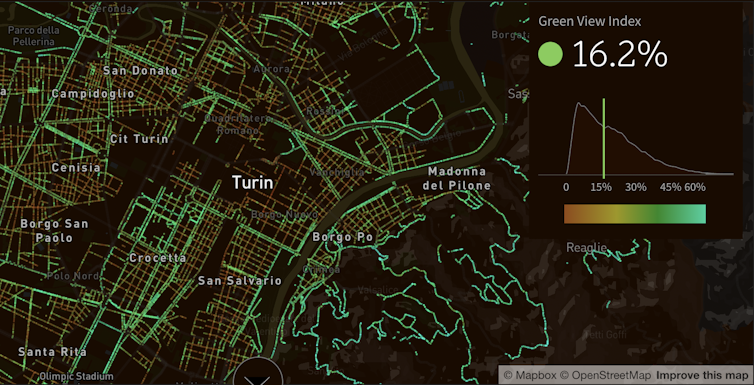

One example of this is the Treepedia research initiative, which was launched in 2016 by Massachusetts-based MIT Senseable City Lab. Treepedia aspires to raise awareness of urban forests by the use of digital vision techniques based on Google Street View images.

Treepedia focuses on pedestrian street trees found in multiple cities around the world, as opposed to parks. The main reason is that pedestrians are more likely to see street trees without planning to, whereas most people in parks made an active choice to be there. Using an open-source library, Treepedia means the public can calculate the quantities of tree coverage for their own city or region.

If urban planners become more aware of the potential of digital technology, then urban green spaces should have a bright future. However, designing the optimal green space that we want for our cities may also call for a deeper future collaboration between urban planners and engineers.

Anthony Larsson, Researcher, Innovation Management, Karolinska Institutet and Andreas Hatzigeorgiou, Affiliate Researcher, School of Architecture and the Built Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.