How does Earth stop meteors from hitting Earth and hurting people?

–Asher, 6 years 11 months, New South Wales

Alright, let’s embark on a meteor adventure! Meteors can sound scary but I promise you they aren’t. Meteors are just cosmic rocks falling into Earth’s atmosphere from outer space. Now, these aren’t any old boring rocks. We’re talking about pieces of asteroids, comets and even fragments from other planets crashing into Earth.

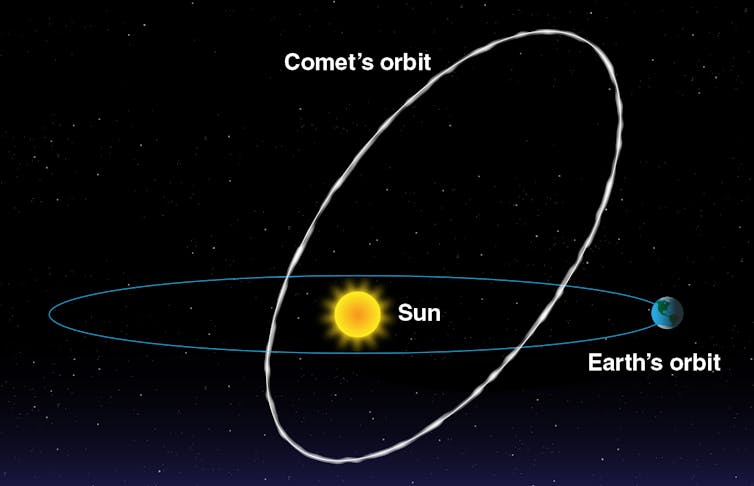

There are also certain times of the year when we experience something called a meteor shower. Imagine Earth is cruising along its normal orbit around the Sun when suddenly it passes through the leftover pieces of rock from a comet or asteroid.

Comets and asteroids shed bits and bobs of themselves along their journey as they get closer to the Sun. When Earth zips through this trail of space debris, meteors streak across the sky like shooting stars.

Meteors have been seen by humans all throughout history and have even been described as nature’s fireworks. Scientists estimate that over 17,000 meteors fall to Earth each year. So, why don’t they hurt us?

Why don’t meteors hit us all the time?

When meteors light up the sky, we’re actually seeing our planet’s remarkable defence system jumping into action.

When a meteor enters Earth’s atmosphere – the layer of air that surrounds us – it meets resistance from the air molecules. This is called friction, and it causes the meteor to quickly heat up.

Remember, a meteor is a piece of rock. The friction heats the rock up so much, it burns and turns into a vapour (sort of like steam). This is what causes the bright streak of a “shooting star”.

Our atmosphere is so good at destroying meteors, around 90–95% of them don’t even reach the ground.

What happens if a meteor goes through the atmosphere?

You might now be wondering – what about the 5–10% of meteors that do survive the atmosphere? Well, if they survive, they become “meteorites”.

The good news is that most of the time, meteorites either land in the ocean or away from humans. There are only two records in the history of all humans of someone being hit by a meteorite.

You have a one in 700,000 chance of a meteor hurting you. In comparison, you have a one in 15,300 chance of being struck by lightning.

The bad news is that meteorites have caused some harm in the past – just look at the dinosaurs. But this only happens when a meteor is really, really large and doesn’t completely burn up in the atmosphere. The chances of such a space rock hitting Earth are very low, but never zero.

So how do we stop them?

Unlike the dinosaurs, we now have big telescopes watching our skies all the time. Astronomers keep track of any large asteroids or comets that could potentially hurt Earth.

The amazing thing is that with our 21st century technology, we don’t just have to rely on Earth’s atmosphere protecting us, we can also protect ourselves.

It’s not expected that in the next 100 years we’ll be in any major danger from a meteorite, but that hasn’t stopped us from planning.

One idea is that we could just redirect a dangerous asteroid in the future.

NASA has already shown the world it can be done. In 2022, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test or DART successfully showed humans can deflect an asteroid – by crashing a spacecraft into the spare rock, it would slowly change its speed and direction.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

Sara Webb, Lecturer, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.