Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

If the James Webb telescope was 10 times more powerful, could we see the beginning of time? – Sam H., age 12, Prosper, Texas

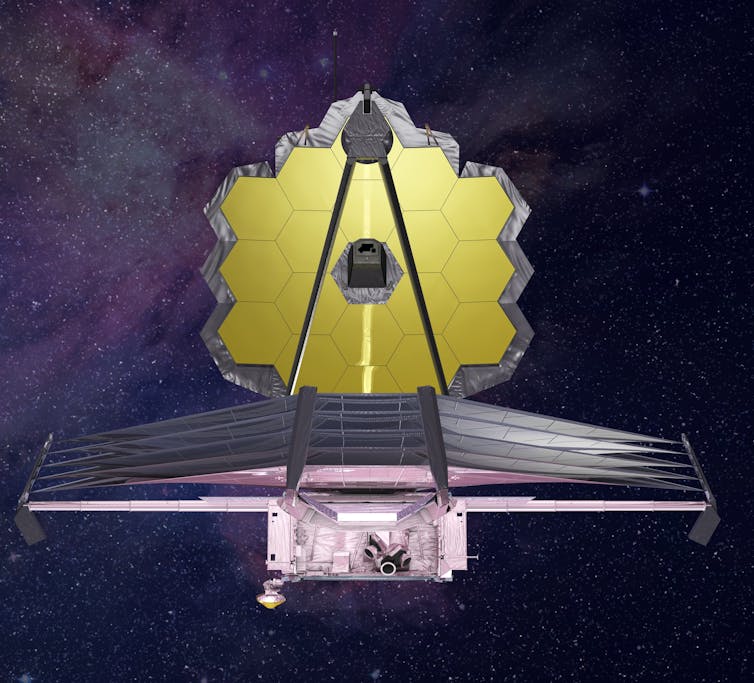

The James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST for short, is one of the most advanced telescopes ever built. Planning for JWST began over 25 years ago, and construction efforts spanned over a decade. It was launched into space on Dec. 25, 2021, and within a month arrived at its final destination: 930,000 miles away from Earth. Its location in space allows it a relatively unobstructed view of the universe.

The telescope design was a global effort, led by NASA, and intended to push the boundaries of astronomical observation with revolutionary engineering. Its mirror is massive – about 21 feet (6.5 meters) in diameter. That’s nearly three times the size of the Hubble Space Telescope, which launched in 1990 and is still working today.

It’s a telescope’s mirror that allows it to collect light. JWST’s is so big that it can “see” the faintest and farthest galaxies and stars in the universe. Its state-of-the-art instruments can reveal information about the composition, temperature and motion of these distant cosmic objects.

As an astrophysicist, I’m continually looking back in time to see what stars, galaxies and supermassive black holes looked like when their light began its journey toward Earth, and I’m using that information to better understand their growth and evolution. For me, and for thousands of space scientists, the James Webb Space Telescope is a window to that unknown universe.

Just how far back can JWST peer into the cosmos and into the past? About 13.5 billion years.

Time travel

A telescope does not show stars, galaxies and exoplanets as they are right now. Instead, astronomers are catching a glimpse of how they were in the past. It takes time for light to travel across space and reach our telescopes. In essence, that means a look into space is also a trip back in time.

This is even true for objects that are quite close to us. The light you see from the Sun left it about 8 minutes, 20 seconds earlier. That’s how long it takes for the Sun’s light to travel to Earth.

You can easily do the math on this. All light – whether sunlight, a flashlight or a light bulb in your house – travels at 186,000 miles (almost 300,000 kilometers) per second. That’s just over 11 million miles (about 18 million kilometers) per minute. The Sun is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) from Earth. That comes out to about 8 minutes, 20 seconds.

But the farther away something is, the longer its light takes to reach us. That’s why the light we see from Proxima Centauri, the closest star to us aside from our Sun, is 4 years old; that is, it’s about 25 trillion miles (approximately 40 trillion kilometers) away from Earth, so that light takes just over four years to reach us. Or, as scientists like to say, four light years.

Most recently, JWST observed Earendel, one of the farthest stars ever detected. The light that JWST sees from Earendel is about 12.9 billion years old.

The James Webb Space Telescope is looking much farther back in time than previously possible with other telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope. For example, although Hubble can see objects 60,000 times fainter than the human eye is able, the JWST can see objects almost nine times fainter than even Hubble can.

The Big Bang

But is it possible to see back to the beginning of time?

The Big Bang is a term used to define the beginning of our universe as we know it. Scientists believe it occurred about 13.8 billion years ago. It is the most widely accepted theory among physicists to explain the history of our universe.

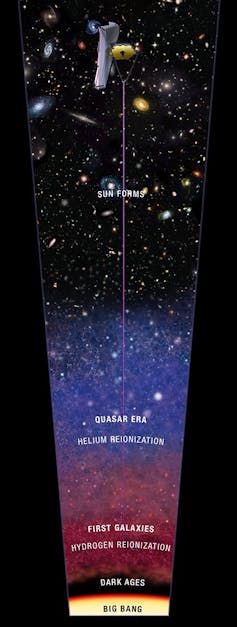

The name is a bit misleading, however, because it suggests that some sort of explosion, like fireworks, created the universe. The Big Bang more closely represents the appearance of rapidly expanding space everywhere in the universe. The environment immediately after the Big Bang was similar to a cosmic fog that covered the universe, making it hard for light to travel beyond it. Eventually, galaxies, stars and planets started to grow.

That’s why this era in the universe is called the “cosmic dark ages.” As the universe continued to expand, the cosmic fog began to rise, and light was eventually able to travel freely through space. In fact, a few satellites have observed the light left by the Big Bang, about 380,000 years after it occurred. These telescopes were built to detect the splotchy leftover glow from the Big Bang, whose light can be tracked in the microwave band.

However, even 380,000 years after the Big Bang, there were no stars and galaxies. The universe was still a very dark place. The cosmic dark ages wouldn’t end until a few hundred million years later, when the first stars and galaxies began to form.

The James Webb Space Telescope was not designed to observe as far back as the Big Bang, but instead to see the period when the first objects in the universe began to form and emit light. Before this time period, there is little light for the James Webb Space Telescope to observe, given the conditions of the early universe and the lack of galaxies and stars.

Peering back to the time period close to the Big Bang is not simply a matter of having a larger mirror – astronomers have already done it using other satellites that observe microwave emission from very soon after the Big Bang. So, the James Webb Space Telescope observing the universe a few hundred million years after the Big Bang isn’t a limitation of the telescope. Rather, that’s actually the telescope’s mission. It’s a reflection of where in the universe we expect the first light from stars and galaxies to emerge.

By studying ancient galaxies, scientists hope to understand the unique conditions of the early universe and gain insight into the processes that helped them flourish. That includes the evolution of supermassive black holes, the life cycle of stars, and what exoplanets – worlds beyond our solar system – are made of.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Adi Foord, Assistant Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.