Two major astronomy research programs, called EMU and PEGASUS, have joined forces to resolve one of the mysteries of our Milky Way: where are all the supernova remnants?

A supernova remnant is an expanding cloud of gas and dust marking the last phase in the life of a star, after it has exploded as a supernova. But the number of supernova remnants we have detected so far with radio telescopes is too low. Models predict five times as many, so where are the missing ones?

We have combined observations from two of Australia’s world-leading radio telescopes, the ASKAP radio telescope and the Parkes radio telescope, Murriyang, to answer this question.

The gas between the stars

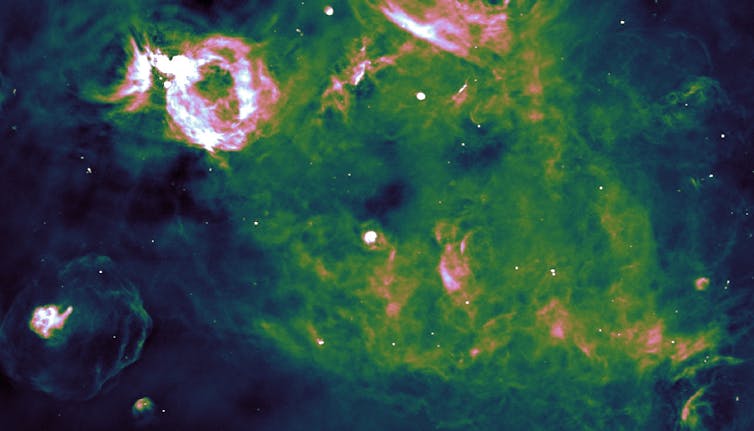

Images: R. Kothes (NRC) and E. Carretti (INAF).

The new image reveals thin tendrils and clumpy clouds associated with hydrogen gas filling the space between the stars. We can see sites where new stars are forming, as well as supernova remnants.

In just this small patch, only about 1% of the whole Milky Way, we have discovered more than 20 new possible supernova remnants where only seven were previously known.

These discoveries were led by PhD student Brianna Ball from Canada’s University of Alberta, working with her supervisor, Roland Kothes of the National Research Council of Canada, who prepared the image. These new discoveries suggest we are close to accounting for the missing remnants.

So why can we see them now when we couldn’t before?

The power of joining forces

I lead the Evolutionary Map of the Universe or EMU program, an ambitious project with ASKAP to make the best radio atlas of the Southern Hemisphere.

EMU will measure about 40 million new distant galaxies and supermassive black holes, to help us understand how galaxies have changed over the history of the universe.

Early EMU data have already led to the discovery of odd radio circles (or “ORCs”), and revealed rare oddities like the “Dancing Ghosts”.

For any telescope, the resolution of its images depends on the size of its aperture. Interferometers like ASKAP simulate the aperture of a much larger telescope. With 36 relatively small dishes (each 12m in diameter) but a 6km distance connecting the farthest of these, ASKAP mimics a single telescope with a 6km wide dish.

That gives ASKAP a good resolution, but comes at the expense of missing radio emission on the largest scales. In the comparison above, the ASKAP image alone appears too skeletal.

To recover that missing information, we turned to a companion project called PEGASUS, led by Ettore Carretti of Italy’s National Institute of Astrophysics.

PEGASUS uses the 64m diameter Parkes/Murriyang telescope – one of the largest single-dish radio telescopes in the world – to map the sky.

Even with such a large dish, Parkes has rather limited resolution. By combining the information from both Parkes and ASKAP, each fills in the gaps of the other to give us the best fidelity image of this region of our Milky Way galaxy. This combination reveals the radio emission on all scales to help uncover the missing supernova remnants.

Linking the datasets from EMU and PEGASUS will allow us to reveal more hidden gems. In the next few years we will have an unprecedented view of almost the entire Milky Way, about a hundred times larger than this initial image, but with the same level of detail and sensitivity.

We estimate there may be up to 1,500 or more new supernova remnants yet to discover. Solving the puzzle of these missing remnants will open new windows into the history of our Milky Way.

ASKAP and Parkes are owned and operated by CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, as part of the Australia Telescope National Facility. CSIRO acknowledge the Wajarri Yamaji people as the Traditional Owners and native title holders of Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara, the CSIRO Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory, where ASKAP is located, and the Wiradjuri people as the traditional owners of the Parkes Observatory.

Andrew Hopkins, Professor of Astronomy, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.