At a Glance

- Two new studies offer a groundbreaking look at “slow earthquakes,” revealing their complex and dual role in managing seismic stress along Japan’s hazardous Nankai Trough subduction zone.

- One team utilized advanced seafloor sensors to discover that slow slip events can act as tectonic shock absorbers, safely releasing built-up energy in hazardous tsunami zones.

- However, a second study presented compelling evidence that a different slow slip event may have triggered a moderate earthquake by transferring stress to a locked fault section.

- These combined findings reveal the dual nature of slow earthquakes, which can either dissipate dangerous seismic strain or dangerously concentrate it, pushing a fault closer to failure.

- This knowledge is vital for assessing seismic hazards globally, especially at faults like Cascadia, where a lack of slow slip activity could signal that immense strain is building.

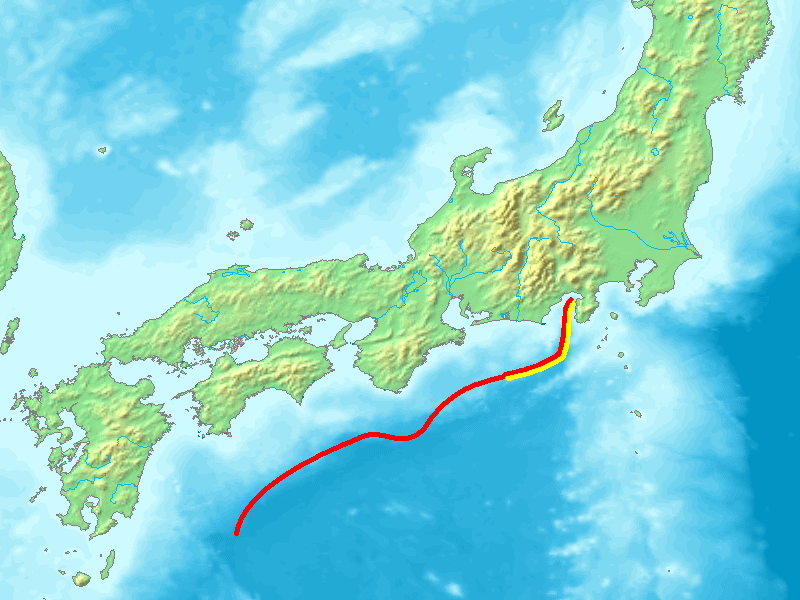

In a significant step forward for earthquake science, researchers have captured a detailed picture of slow-motion earthquakes, also known as “slow slip events,” unfolding deep beneath the ocean. Two new studies published in the journal Science (1, 2) provide a new understanding of these quiet but powerful events along Japan’s Nankai Trough, a 900-kilometer-long subduction zone known for generating massive earthquakes and tsunamis. A subduction zone is an area where one of Earth’s tectonic plates slides beneath another. These findings reveal the complex role slow slips play in distributing tectonic stress, sometimes relieving pressure and other times potentially setting the stage for a major rupture.

One research team used highly sensitive instruments installed in boreholes drilled into the seafloor to monitor the fault directly. They observed slow slip events behaving like a tectonic shock absorber, slowly unzipping a section of the fault over several weeks. The data revealed a definitive link between these slow slips and areas of high pore fluid pressure. In this condition, water trapped within rock pores reduces friction, allowing the plates to creep past each other instead of breaking violently. This process appears to harmlessly release built-up energy in the shallowest part of the fault, the same region where sudden slips can trigger devastating tsunamis.

However, a second study highlights the dual nature of these events. By tracking land deformation, another group of scientists found evidence that a slow slip event may have triggered the magnitude 6.7 Hyuga-nada earthquake in 2024. This suggests that while slow slips can dissipate stress in one area, they can also transfer that stress to an adjacent, “locked” portion of the fault, pushing it closer to failure. Together, the studies show that slow earthquakes are a critical and complex factor in the earthquake cycle, acting as both a safety valve and a potential trigger.

These discoveries have crucial implications for assessing seismic risk globally, particularly at other major subduction zones. For example, the Cascadia subduction zone off the coast of the U.S. Pacific Northwest, which is capable of producing a magnitude 9 earthquake, appears to lack the same kind of slow slip activity in its shallowest regions. This “deadly silence,” as researchers describe it, could indicate that the fault is completely locked and accumulating strain. The success of the Nankai monitoring effort underscores the urgent need to deploy similar deep-ocean observatories in other high-risk areas to understand better and prepare for future seismic hazards.

References

- Edgington, J. R., Saffer, D. M., & Williams, C. A. (2025). Migrating shallow slow slip on the Nankai Trough megathrust captured by borehole observatories. Science, 388(6754), 1396–1400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ads9715

- Obara, K. (2025). Where slow and large earthquakes meet. Science, 388(6754), 1369–1370. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ady7173

- University of Texas at Austin. (2025, June 26). Scientists capture slow-motion earthquake in action. Phys.Org; University of Texas at Austin. https://phys.org/news/2025-06-scientists-capture-motion-earthquake-action.html